-

Remembering those at Mansfield Training School…

Disclaimer: The MTS Memorial Museum website is currently under construction, as we continue to learn more about Mansfield Training School and its residents. During this time, we intend to place the accessibility of our website at the forefront as we aim to work in coordination with UConn’s IT Accessibility office to complete a holistic access review of all components of the MTS Memorial Museum website. Thank you!

The Mansfield Training School Memorial Museum aims to preserve the nearly erased, and over 100-year long, history of the Mansfield Training School in order to remember the lives, voices, and experiences of those who were institutionalized here. With deep-rooted cross-institutional connections to universities, hospitals, and government agencies across the State of Connecticut, the Mansfield Training School and its history reveals the treatment, attitudes, and discrimination experienced by people with disabilities throughout the 20th century, up until its closure in 1993.

Image Description:

The first five photos from Mansfield Training School are in black and white and are largely from the first half of the 20th century.

Image 1: The first photo shows six girls in a line, dancing in flowy dresses outside on the MTS lawn (1939).

Image 2: The next photo is of the former superintendent of MTS, Neil A. Dayton, with 17 men dressed in suits, standing and sitting around the blueprints for a newly constructed dorm hall on the grounds of Mansfield Training School.

Image 3: Watching as the previous blueprints become a reality, we have the newly constructed dorm area for residents in the third photo. It depicts about 19 beds for residents, packed tightly together in groups of two and three, separated only by a metal chair and night stand. Each group of beds is separated from the rest by a very short metal partition offering very little for privacy.

Image 4: The fourth photo shows the laundry room at MTS. Here, women are working on washing and ironing the clothing. Many residents worked in these laundry rooms during their time as residents of MTS.

Image 5: The last black and white photo is of a UConn student volunteer cutting a resident’s hair as she sits at a round wooden table in what appears to be a library. Over the course of the last five to ten years of its operation, UConn sent over 300 volunteers to MTS for a wide array of programs.

The last two photos are from 2022 and are in color.

Image 6: The first photo is of an unmarked brick building with a metal chain-link fence around it. Some of the windows of the building are broken and others are painted with spray paint graffiti. Several of the windows also have what seem to be curtains left hanging from when MTS was operational, now sunbleached and decayed to the point of near-transparency.

Image 7: The final photo shows a closer view of the brick building, with a tree growing out of a broken window. In the window next to the tree hangs more curtains, very weathered.

Mansfield Training School Today

As of today, many of the abandoned buildings across the 350-acre MTS campus remain untouched since their closure. Transferred to the University of Connecticut in 1994, the buildings once served as storage for the university but due to lack of maintenance, they continue to deteriorate. MTS today is known by many students for its “haunted” nature, however few know the true history of the lives of those who lived here…

Image Description: Pictured on the left is a black and white image of Knight Hospital, built-in 1860. To the right, an image of the inside of Knight Hospital in 2022. Decayed after years of abandonment, the sun shines through very large holes in the ceiling and leaves, trash, and old furniture litter the floor below. Latest Posts and Updates

- Experiencing the Archives!

- MTS Team Live Reading: “The Mansfield Training School Is Closed: The Swamp Has Been Finally Drained” by Roger D. MacNamara

- Places of Waiting

- In the Archives…

- Why I’m Here -Brenda

-

Why I’m Here: Where Have We Been, And Where Are We Going? -Jess

As we round closer and closer to the day this project (or at least the idea for it) began just two years ago, I honestly still can’t believe this is just the beginning. To me, the years we spent working, researching, writing, and thinking just blurred together. Every moment leading to this blog was a learning experience—a time to sit back, listen, learn, and try to understand the history of MTS and how we can best engage with the residents who still live today. Community should always be at the center of any restorative justice project. And, there are always moments that stick out even in these very early moments. The moments that grab you by the shoulders and shake you awake: realizing how large of an impact UConn had on the lives of residents at MTS, discovering pages upon pages of documented charitable donations without seeing a single narrative from a resident themselves, and discovering just how many medical violations, malpractices, and insufficient documentation occurred at MTS. In truth, I never knew what would spur out of this project or where we’d go from here.

I can’t help but think, though, that despite the past year this is really just the beginning.

On September 24th, 2021, I scheduled my first appointment to view the Mansfield Training School files at the Dodd Center for Human Rights. Following my meeting with Brenda that served as a catalyst for this project surrounding what happened to Mansfield Training School a week prior, I went in with the mindset of if I find anything about MTS then maybe we could see how UConn’s history with disability began to form into what we see today.

Brenda and Jess in the Connecticut State Library Archives in 2022, viewing black and white photo boards taken of MTS residents from the 1960s. Traditionally, higher education has always been an institution where millions of disabled students have felt discriminated against due to the lack of access, support, and acceptance of disability culture/identity in university spaces. I can personally attest to this feeling. I wanted to know, as a student, where UConn had been. At first, I wanted to see some semblance of the past, some bit of history I could see that would give me any inclination as to why so many of us faced bias and discrimination on-campus.

What was UConn’s connection to disability historically?

At first, I wasn’t too hopeful I’d find the answer. After combing through search after search on Google, Bing, Yahoo (you name the search engine, I tried it) I really couldn’t find much on UConn’s connection to the Mansfield Training School at all. It almost felt like any remains of the institution, prior to its closure, had been erased. It was simply a thing of the past. A memory.

I was even less hopeful when I learned that the Mansfield Training School files at the Dodd Center only amounted to a few boxes (plus some scattered folders in other collections from the then-president Homer D. Babbidge). I still felt like there was more to the story that we can see online, which mainly consists of ghost hunters and urban explorers breaking into the site to see “ghosts.” After all, UConn was given all of the property of MTS after its closure, at which point it was renamed the “UConn Depot Campus.” So, I started digging through as many files as possible and amped up my online searches.

If I could go back in time to talk to the very-very-new-to-research, freshman scholar version of myself (I’d classify myself as a ‘sophomore’ now…at least…maybe, not even?) I’d tell them that sometimes just one word—a name, an organization, a face—can change the entire course of your research. A single piece can change everything and uncover a vast amount of information that you could never have guessed would have ever existed.

The reason I’m here is to not just learn more about MTS and UConn’s connection through the archives. I’m here because I hope to engage with stories from residents at MTS and learn more about their experiences there. I hope that through this project we can work to center the community and seek the sort of accountability they want to see from a government, university, and institution that was responsible for so much harm. Whether this accountability is through a memorial, reparations, preservation initiative, oral history documentation or film, writings, or any other avenue—I hope that this project can be a first step to creating the change they want to see in Connecticut.

The largest gap across every archival collection that housed history related to MTS was the lack of perspectives from the residents. Those who lived there and spent nearly their entire lives within that campus. After checking nearly every file, folder, or box, not a single narrative came through that wasn’t under the control of administrators from the institution itself. This really made me focus on, and ask:

How do power and privilege play a role in whose stories we see in archival documents and history as a whole?

-

Why I’m Here! -Paula

Hi, I’m Paula! 🙂

As a long-time museum lover, when Brenda reached out with the opportunity to apply to be part of the MTS team, I was immediately intrigued. I’ve always been interested in “untold stories” and the amplification of voices who historically haven’t been heard in different fields. For museums, this was a very clear area for me to explore: when working as an interpreter in high school, my supervisors and mentors were excellent advocates, especially for people who typically weren’t represented at all in the museum sphere. One specific observation that I remember hearing from a coworker was something along the lines of, “Older white men wrote all the stuff in this museum in the 1900s and it never changes. How are we supposed to connect with the information now?”

From there, I realized (as so many other people have before me!) that this applies to almost all areas of our lives–if we don’t have access to a wider array of people’s experiences and stories, then we are limited to an all-too-familiar narrative, which, honestly, most of the time doesn’t click with a lot of people. The MTS project is one of these opportunities to uncover and publicize the stories of people who have been mistreated and silenced, and I am more than honored to be a part of the awesome team that’s working so hard to give those stories a platform.

-

Why I’m Here-Lillian

I fell in love with the archives after touring the university’s shelves. The vast amounts of material in particular drew me in, the amount of information held on those shelves was staggering.

The stories hidden within the shelves fascinated me as did their preservation. As a history major I knew the importance of reading, of remembering, of recording. That is how history is passed down and preserved.

I knew I wanted to intern this summer but I struggled to find a position that really drew me in. Then I found this apprenticeship. It had each piece I was looking for. It gave me the opportunity to explore the archives, to help tell a story that needs to be told, and to work with a great team. The fact that MTS is so close to where I go to school also drew me in, as it gave me the chance to explore the history of my own community, especially history that was not properly memorialized.

-

Hauntings and Horror: Institutionalization and the Urge to Embrace the Paranormal

By: Jess Gallagher

“[D]espite the mostly positive, caring work that went on here

(and at other similar facilities), there seems to be a story or two of negative incidents,

any one of which is enough to initiate stories

of restless souls and troubled spirits.”

–Damned Connecticut

“Mansfield Training School has gotten plenty of attention,

for it is believed to be haunted.”

–Abandoned Playgrounds

“A former mental asylum still haunted by its victims…

Dead animal bones littered the area.

Old dressers, beds, and a wheelchair were strewn all over.

The antique board reading “The Mansfield Training School”

–Syfy’s Paranormal Witness “The Haunting of Mansfield Mansion”

It was around 8:30 p.m. on a Monday night in early March. I sat at my desk in our school newspaper’s office. Since I had finished copyediting a good portion of my work for next day’s paper, I spent the rest of my free time line-editing a draft of my honors thesis on Mansfield Training School. Of course, while this was months later than my initial research on the institution, there were still more than a few questions that were left unanswered despite the amount of archival work that we had done. So, naturally, whenever I hear the words “Depot Campus” come out of someone’s mouth I instantly start listening, but I normally always hear the same conversation repeated…

“Oh yeah, have you guys ever been to the Depot campus before.”

“No, what’s that?”

“Isn’t that where the puppet place is?”

“Yeah, I heard it’s pretty haunted.”

This is how most of the conversations I overhear go. And, while it’s interesting to hear people actually talking about Mansfield Training School, this specific conversation really made me start thinking about hauntings and the implications that these narratives have on the past. Though the “haunted” articles on Mansfield Training School outweighed the history on my initial search of the school I really didn’t think much of it. It’s so common after all.

Image Description: Screenshot from the “Paranormal Witness” wiki fandom on Mansfield Training School Growing up, I always listened to stories about old hospitals, abandoned prisons, and “insane” asylums. My friends and I watched Paranormal Witness, The Haunted, and Ghost Hunters. And while these shows did tell us a little bit about the history of the buildings and sites they investigated, the main emphasis was on the demonic, the anger, the aggression, and the ‘ghosts’ rather than the people who endured the abuse, suffering, and oppression that those in power inflicted on them.

In a way, we almost fail to understand the social impact that articles on “hauntings” have when it comes to the United States’ history of institutionalization. Viewing historical sites as “haunted” almost creates distance between the true history of the institutions and (if done frequently enough) can erase the humanity of the people who come to be labeled as just the institution’s “victims.” They become faceless.

It seems that through the rhetoric utilized when talking about institutionalization if we center hauntings rather than investigate the histories of the “victims” or objects of said haunting, we can lose valuable information that critiques past behaviors and actions, attitudes, and ideals, or spatial and cultural norms that inflicted abuse and supported the oppression of millions of marginalized identities.

Of course, there is always a degree of temporal distance associated with sites such as Mansfield Training School and its history, but if we use distance and re-frame it as a means to gain clarity and perspective that comes with the passage of time then we can establish a relationship of engagement and insight that can connect us to a past that has long been erased.

I am in no way, of course, shaming or demeaning the entire genre of ‘ghost stories’ or ‘hauntings’ by talking about the potential harmful effects that can come when we center and sensationalize paranormal narratives over history and people of the past. The attention garnered by these paranormal stories could very well serve as a launching point for where we, as activists and scholars, can begin working.

But, we must first be conscious of the distance being created (both socially, historically, and culturally) in these paranormal narratives and only then can we truly examine ‘sites of hauntings’ as ‘sites of history.’ In changing that perspective, scholars, activists, and investigators can uplift the stories and histories of those who lost their lives at these institutions.

When we come to understand the history of institutions like Mansfield Training School, we understand that it was not just a place with “mostly positive, caring work” being conducted that just happens to have one or two angry spirits (like Damn Connecticut would have us believe). Instead, we uncover the politics, experimentation, and cross-institutional connections that went on here and in dozens of institutions across the state of Connecticut.

While ghost stories and narratives of the paranormal will always remain, I think it’s important that we remain cognizant of the people behind these narratives, their histories, and work to advocate against modern-day forms of institutionalization that currently exist in our society. If not, then years from now, we may see our own history become one of the many haunted stories of the past…

-

Ambiguity of Responsibility

By: Matthew Iannantuoni

Enraptured by the findings of the termination papers, I dove back into the folders of the “Dismissal and legal action regarding Elly C. Fischer, Florence M. Nichols, James P. Purcell, Dr. Helen T. Warner” where I found another shred of evidence that seems to only muddy the story I was trying to uncover. On a yellowed piece of legal paper was, in faint handwriting “Overheard in staff dining room by patients (waiters) Dorothy Reynolds on the day of the write up in the paper (Tuesday Dec 14 1944.)” This faded note from some unknown staffer details a conversation between the three medical staff members who would be terminated less than a year later. The conversation goes as follows:

“Dr Warner said the paper did not blame him enough”

Mrs. Nichols replied “they’d get something on him yet.”

Mrs Fischer said “He’s such a damn liar he’d deny it anyway”

“The next day Dr. Warner said to Dorothy Reynolds ‘you’d better look out they may send you to the Superintendent’s office’”

She replied, “I wouldn’t go to the office and tell anything.”

Dr Warner said “That’s right Dorothy don’t go”

The girl was told not to tell anything she overheard them talking about in the dining room”

This faded piece of paper gives so much muddying insight into how things at MTS were running at the time. It seems as though the three medical staff members, Warner, Nichols and Fischer all spoke out to a newspaper against Superintendent Neil Dayton, but that the resulting article did not cover all that they were complaining about. The conversation with one of the patients also gives some insight into how Dayton ran the institution; the threat of going to the Superintendent’s office is enough to keep the patient quiet. It really calls into question some of the more intense complaints on the termination letters. Some of the most egregious examples are in Dr. Warner’s termination letter, which states:

“Incompetency in the service in failure to respond to a call in the case of Louise Seymour, who was suffering from a broken femur. You did not go to see the patient, but ordered her brought to the clinic in the Hospital Building. The patient, with a broken leg, was picked up and, although in great pain, was carried to the Hospital Building by another patient”

There is also the complaint:

“Failure to follow an order to the point of insubordination in not writing out orders in Doctor’s Order Book in William Coursen’s case. Five hypodermics were administered by you without being recorded in either the Doctor’s Order Book or the beside notes, with the result that there is no record of the drugs given by hypodermic at these times by you, or the amount thereof.”

While these seem like rather appalling offenses from the director of nursing, there are other shreds of evidence that sway in the direction that Dr. Warner was doing the best she could with limited resources. For example, in a letter from Dayton to the Chairman on the Board of Trustees there is the request to hire a pharmacist because “the work of the Drug Room has been taken care of by Mrs. Nichols and the other registered nurse. However, properly speaking, this is not their work and it has not been a very satisfactory procedure,” Later stating that “We might be in a little better position to stand criticism if we had a pharmacist” of which criticism is probably referring to the newspaper article that started this controversy.

Another piece of damning evidence is the document titled “REASONS FOR EMPLOYEES LEAVING THE: Mansfield State Training School and Hospital March 1– April 30, 1945” which details that a total of 19 staff members had resigned, retired, or left without notice all in the same short period. While there is little explanation left for this mass exodus it seems as though there was some great discontent when only 2 of the 19 left for reasons pointing toward a consensual and mutual break.

As mentioned in my previous blog post, this is the rub in doing this kind of archival work, we are left with a few puzzle pieces that can fit together several different ways. Was it truly a bad set of staff that were not fulfilling their job responsibility? Was it poor leadership that set impossible standards in an attempt to rid the institution of workers speaking out against some cruelty in the institution? Was it some unknown third factor that has been lost to time? Given what we know about how patients were treated at the Mansfield Training School it is important to ask who is to blame, which, of course, is never a cut and dry answer. However, any shred of definitive culpability seems to be lost to time, given the documents left behind.

Image 1: Superintendent Neil A. Dayton.

Image 2: “Overheard in staff dining room by patient.”

Images 3 & 4: The termination letter of Dr. Helen T. Warner.

Images 5 & 6: A letter from superintendent Dayton to the Chairman of the Board of Trustees requesting the hire of a pharmacist in order “to better stand criticism.”

Image 7: “Reasons for Employees Leaving the Mansfield Training School and Hospital March 1- April 30, 1945.”

-

A First Day of Many Questions

By: Matt Iannantuoni

My fellow researchers, Jess and Brenda, had found in the archive inventory list a box titled “Dismissal and legal action regarding Elly C. Fischer, Florence M. Nichols, James P. Purcell, and Dr. Helen T Warner (1942-5.)” Knowing that I am eventually bound for Law School, they suggested I read through it as my entrance into this project. After reading through these folders I have found my problem with this type of archival work is that those doing the research are at once archeologists, storytellers and, ultimately, visitors peaking in on what was once someone’s career. The natural inclination is to put together a story from the documents which tends to be like putting together a puzzle without the picture on the box and with many missing pieces. As I dug through the minutes and court documents from the Personnel Appellate hearings for four employees of Mansfield Training Schools I was trying to find the through-line of the folder, I kept asking, what did these four major staff members do in the mid-forties?

My question had been answered by a slew of new questions when I came upon a stapled set of papers titled “Termination Letters” and the through-line immediately revealed itself, “Failure to cooperate with and hostility towards, and defiance of the authority of the Superintendent duly appointed by this board.” Each of these employees, an X-Ray Technician (Fischer,) the director of nursing (Nichols,) a business manager (Purcell,) and a Senior Physician (Warner) had all been fired, at the same time, for separate and often seemingly inconsequential missteps besides this one similarity- “defiance of the authority of the Superintendent.” Perhaps this common complaint is just a generalized, boilerplate umbrella phrase, however, the explicit mention of the Superintendent (Neil A. Dayton) seems to point away from this conclusion.

Each employee had a laundry list of missteps, such as the director of nursing being accused of “Neglect of duty and incompetency in failure to have resertilized for several months certain sterile goods held for routine or emergency use.” Or, in the case of the X-Ray technician, “Language and conduct towards personnel employed in said institution, leading to friction, dissension, and disturbance of the harmonious operation of the institution.” It’s impossible to say with any certainty how founded or unfounded these claims are, which is the “rub” of doing this kind of work, however, taken with what we know about the overwhelming code of silence which allowed so many cruelties to go on unabated, it seems that those accused may have spoken out against the institution, “broken the code” and were fired soon after.

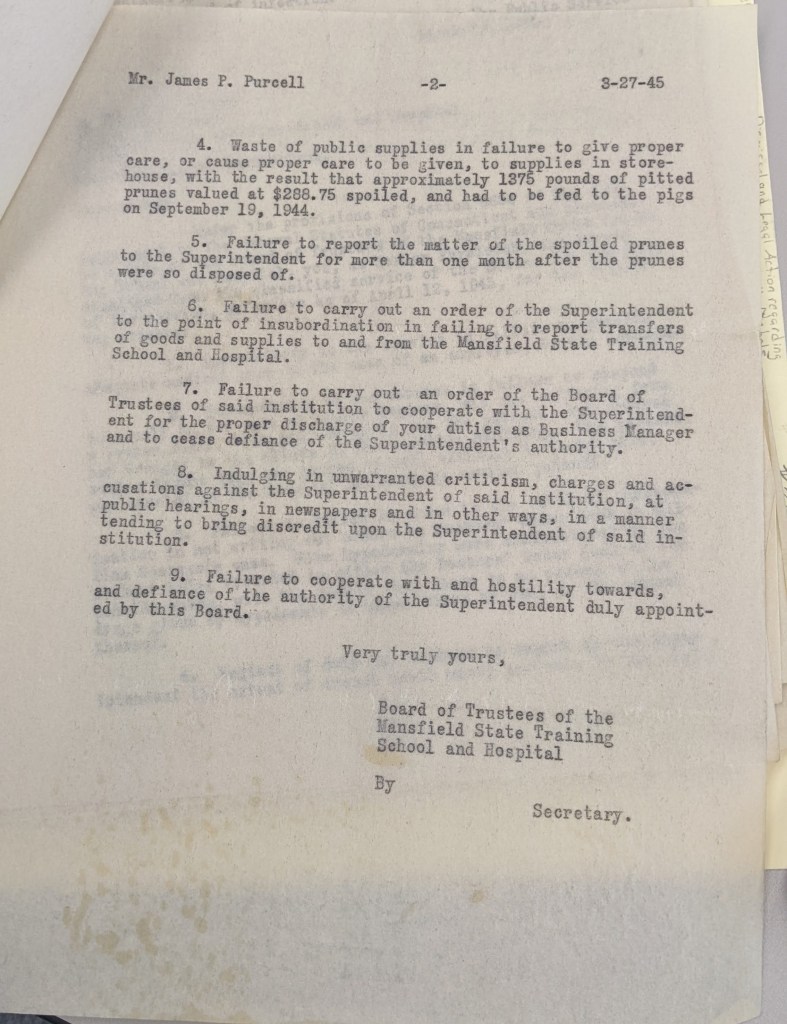

Another “mask off” example of this is in the complaints levied against the business manager (Purcell) which, chief among the nine, is “Failure to carry out an order to the point of insubordination in refusing to return an ornamental metal tray left as a gift in your office in 1943 by a business concern doing business with said institution” and then hidden on the second page, at number 8 is “indulging in unwarranted criticisms, charges and accusations against the Superintendent of said institution, at public hearings, in newspapers and in other ways, in a manner tending to bring discredit upon the Superintendent of said institution.” Attempts to find records of the public hearings, newspapers and the ominously ambiguous “in other ways” proved futile, a moment in MTS history that is left open to interpretation.

As I dug through this box of files I kept finding different documents that did not seem connected to the termination of the staff members, for example, a few patient census files that counted the number of patients at MTS, a copy of an outdated Connecticut act concerning “Training School Recommitments and Transfers,” as well as a letter from the patient’s mother, thanking the Superintendent for the treatment her son received from doctors and nurses. I’m not sure how these relate to the mass termination of 1945, but I’m also not sure why they would be in this folder if they were not. More questions than answers on this first day of research.

Image 1 and 2: the termination letter of business manager James P. Purcell.

Image 3: Thank you note from Tommy’s Mother (name omitted for privacy.)

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.