-

Remembering those at Mansfield Training School…

Disclaimer: The MTS Memorial Museum website is currently under construction, as we continue to learn more about Mansfield Training School and its residents. During this time, we intend to place the accessibility of our website at the forefront as we aim to work in coordination with UConn’s IT Accessibility office to complete a holistic access review of all components of the MTS Memorial Museum website. Thank you!

The Mansfield Training School Memorial Museum aims to preserve the nearly erased, and over 100-year long, history of the Mansfield Training School in order to remember the lives, voices, and experiences of those who were institutionalized here. With deep-rooted cross-institutional connections to universities, hospitals, and government agencies across the State of Connecticut, the Mansfield Training School and its history reveals the treatment, attitudes, and discrimination experienced by people with disabilities throughout the 20th century, up until its closure in 1993.

Image Description:

The first five photos from Mansfield Training School are in black and white and are largely from the first half of the 20th century.

Image 1: The first photo shows six girls in a line, dancing in flowy dresses outside on the MTS lawn (1939).

Image 2: The next photo is of the former superintendent of MTS, Neil A. Dayton, with 17 men dressed in suits, standing and sitting around the blueprints for a newly constructed dorm hall on the grounds of Mansfield Training School.

Image 3: Watching as the previous blueprints become a reality, we have the newly constructed dorm area for residents in the third photo. It depicts about 19 beds for residents, packed tightly together in groups of two and three, separated only by a metal chair and night stand. Each group of beds is separated from the rest by a very short metal partition offering very little for privacy.

Image 4: The fourth photo shows the laundry room at MTS. Here, women are working on washing and ironing the clothing. Many residents worked in these laundry rooms during their time as residents of MTS.

Image 5: The last black and white photo is of a UConn student volunteer cutting a resident’s hair as she sits at a round wooden table in what appears to be a library. Over the course of the last five to ten years of its operation, UConn sent over 300 volunteers to MTS for a wide array of programs.

The last two photos are from 2022 and are in color.

Image 6: The first photo is of an unmarked brick building with a metal chain-link fence around it. Some of the windows of the building are broken and others are painted with spray paint graffiti. Several of the windows also have what seem to be curtains left hanging from when MTS was operational, now sunbleached and decayed to the point of near-transparency.

Image 7: The final photo shows a closer view of the brick building, with a tree growing out of a broken window. In the window next to the tree hangs more curtains, very weathered.

Mansfield Training School Today

As of today, many of the abandoned buildings across the 350-acre MTS campus remain untouched since their closure. Transferred to the University of Connecticut in 1994, the buildings once served as storage for the university but due to lack of maintenance, they continue to deteriorate. MTS today is known by many students for its “haunted” nature, however few know the true history of the lives of those who lived here…

Image Description: Pictured on the left is a black and white image of Knight Hospital, built-in 1860. To the right, an image of the inside of Knight Hospital in 2022. Decayed after years of abandonment, the sun shines through very large holes in the ceiling and leaves, trash, and old furniture litter the floor below. Latest Posts and Updates

- Experiencing the Archives!

- MTS Team Live Reading: “The Mansfield Training School Is Closed: The Swamp Has Been Finally Drained” by Roger D. MacNamara

- Places of Waiting

- In the Archives…

- Why I’m Here -Brenda

-

Poetry of the Institution– A Closer Look of MacNamara’s Poetics

Written By Madison Bigelow

During Summer 2023, the entire research team co-authored a blogpost with our own reflections on Superintendent Roger D. MacNamara’s analysis of the Mansfield Training School closure in 1993, titled “The Mansfield Training School Is Closed: The Swamp Has Finally Been Drained.” Warmly referred to by our own team as “Dayton Drains the Swamp,” this op-ed explores what seems to be MacNamara’s attempt to make peace with his own involvement in the atrocities that took place during his time as head of MTS’ administration.

Amongst the many fascinating things that MacNamara has to say about the school’s closure and his experiences as superintendent, something that deeply struck me about his piece comes near the beginning of the article: a quote he includes from the book titled Souls in Extremis (1971), which is Burton Blatt’s analysis of the inhumane conditions of institutions that house the mentally and/or physically disabled. MacNamara introduces this quote by stating that “Blatt included a piece of my free verse in the foreword [of his book].”

On the first page of MacNamara’s editorial piece “The Mansfield Training School Is Closed: The Swamp Has Finally Been Drained,” he includes an excerpt from Burton Blatt’s Souls in Extremis (1971).

The quote reads: “Backward stranger, you have story to tell without words we can understand. Never thought to possess human needs,your only gifts are isolation and desolation. Your life in a porcelain cage is nonexistence, interrupted only by the madness of your sisters’ struggling spirits. Can you hear the people talk of change only to see compassion left at the door step? How could you know that the reforms never left committee? Growing old and inwardly dying each passing day, why can’t you accept injustice in silent agony, as we were told you would. The sands of time create the glass you shatter, and you turn on your own irreplaceable flesh in self-inflicted torture, which on one understands to be your message to the planners: ‘I will render my flesh disfigured and blur my consciousness while you are powerless to stop me. Your consciences do not allow you to bind me, but your senses cannot tolerate my destruction. When you find the answers and have the means, I will be waiting here for my new life. I’m not going anywhere.’”To be frank, my eyes sort of glazed over this portion of the op-ed when I read it on my own. Because this quote appears on the first of four pages, I found myself skimming over this portion to find his direct criticisms of the Mansfield institution. However, hearing Brenda speak these words out loud during our group-read of the piece, I started to become deeply curious about the rhetorical implications of MacNamara’s choice.

It is important to note that this quote is, in fact, an excerpt written by MacNamara himself that appears in Burton’s forward (which… must’ve required a lot of self-admiration, to say the least). To acknowledge that this quote is explicitly and intentionally written in free verse begs the question: why does a poem appear in the middle of MacNamara’s serious meditations on MTS’ shutting down for good?

Granted, this excerpt doesn’t read like a poem in the most ‘traditional’ sense. It lacks any sort of end-rhyme scheme, line breaks, or a ‘standard’ rhythmic cadence that one would expect from poetry. However, MacNamara explicitly notes this quote as a work of free-verse. Maybe this is a fast and loose employment of the term. But, especially since MacNamara acknowledges his own writing (and the intent behind it) as a work of free-verse in “Dayton Drains the Swamp,” I think it deserves the respect of being read as poetry, if just for a thought experiment.

To perform a brief analysis on the excerpt above, MacNamara’s ultimate goal in his self-quotation is to foster a deep-seated feeling of sympathy towards the residents of Mansfield. The repeated address of the second person implicates the audience in temporarily assuming the role of the disenfranchised; as MacNamara asks “Can you hear the people talk of change only to see compassion left at the door step?” to leverage the viscerality of his audience’s sympathy for the residents that is much quieter in the rest of the piece.

In the second half of the poem, he switches perspective and adopts the voice of the institutionalized. Concluding the excerpt with the statement “‘When you find the answers and have the means, I will be waiting here for my new life. I’m not going anywhere,’” MacNamara further calls upon the sentimentality of his audience in a very interesting way; he assigns and articulates the voice of the masses that have been excluded from the conversation of deinstitutionalization up until this point in time. A voice, in other words, that many have been willing to argue ‘for the sake of’ but very hesitant to listen to.

The use of metaphor here, too, is particularly thought-provoking. In such a clinical, sterile, and otherwise professional space that was the Mansfield Training School, a former leader of the administration himself chooses figurative expression above any other method to communicate his thoughts regarding institutionalization. While he cites concrete observations about the abuses, corruptions, and hypocrisies of MTS later in the op-ed, the choice to firstly ground his position with a poetic excerpt speaks volumes.

Comparing life in the institution to “life in a porcelain cage [as] nonexistence, interrupted only by the madness of your sisters’ struggling spirits” suggests that the happenings at public institutions across the country are almost too atrocious to be spoken about. By adopting such a poetic vehicle to exemplify the deepest iterations of these abuses upon residents housed in these facilities, it seems that MacNamara specifically utilizes free verse as a vehicle for expressive thought when other methods have failed.

I acknowledge, though, that this insight is completely formed as a result of my biases– I love poetry, and I look for poetry in everything. Maybe even in places where poetry doesn’t ‘exist’ (although, that’s another conversation). However, the intentional use of poetry as a tool to approach institutionalization and the humanity of its residents that is integral to remember, but often forgotten, cannot be ignored. Despite all of the legal proceedings, government hearings, and standard procedures that illuminate the legacy of the Mansfield Training School, the actual ‘issues’ surrounding MTS concerned people. People with emotions, with feelings, and with experiences that can’t be genuinely shared in an administrator’s testimony.

To me, MacNamara tries to voice the experiences of others – specifically the institutionalized that have been denied their voice from the origin of MTS to its closure – and mobilizes poetry as a means to convey a sympathetic appeal to his audience similar to if a resident would have spoken. Of course, his attempt isn’t perfect. Clearly, the excerpt is written by an individual who is very well-read and has knowledge of life inside AND outside the institution from a bird’s-eye view.

But MacNamara pulls back the curtain, if only for a brief moment, and sheds light on the possible emotional state of many residents themselves. In an ideal world, residents and others involved in institutional life would be directly invited to these testimonies, conferences, and other conversations concerning their ‘well-being’ and trajectory of their institution. This clearly didn’t happen, or else we would see residents’ names in the historical records. However, MacNamara does provide an insight to his colleagues and peers about the internal soul of the institution that they presumably would’ve never considered otherwise, had it not come from his mouth.

Ultimately, metaphors resonate; they’re able to explicate and convey iterations of the human experience that could never be contained by a standard procedure. And, as a whole, poetry illuminates. It elucidates sentiment, sensation, and incidence. Establishing these metaphors sets the tone of the piece and serves as an emotional anchor point for many of the events leading to MTS’ closure in the 90s.

-

In the Archives…

Written By Madison Bigelow

Never in a million years did I think that I’d be given the opportunity to do archival research. Even prior to two years ago, I didn’t realize that there was “research” to be done in the humanities (I use scare quotes here because of course there’s research to be done everywhere, I was just personally chained to the assumption that research only happens inside a science lab).

Throughout the series of archival visits we did during May-June 2023 together, my day always began the same: waking up at 6:30 am in my bed in New Jersey, hopping in the car by 7:30 am, and hoping that I’d make the 10:30 am meeting time the team had agreed upon in Hartford, CT. Other than the long drives I knew I had ahead of me, I had no further expectations for what it would be like to be working with some historical documents that, in reality, are the same age as my parents.

While we were able to view so much material, collectively, over our five visits to the Connecticut State Libraries archival warehouse, there was even more in the archives that we weren’t able to touch. Partially, that was just an issue of time, but the CSL warehouse also houses a large volume of legally redacted documents that archivists just haven’t been able to review yet, and therefore, couldn’t be handed over to our research team.

My biggest takeaway from working in the archives has been reflecting on how deeply emotional this process has been for me. Usually, I feel like the term “research” connotes feelings of sterility, scientific precision, and white lab coats. However, my personal experience has yielded so much more than solely the MTS’ collection of archival information. To hold someone else’s history in your hands is an indescribable feeling; it only becomes more visceral upon the realization that those same people were unable to voice their own stories, and those many stories tucked away in the CSL warehouse (and beyond) might fit together to shed just a bit of light on the largely forgotten legacy of the Mansfield Training School. It’s a feeling that I frequently remind myself as I reflect on that time I spent in the archives this summer, whether I’m working on a post for the memorial blog or just sitting at the dinner table. Even more so, it’s a feeling that renders me with a complete sense of awe and appreciation for the work that Jess, Brenda, and the rest of our research team has been able to accomplish in terms of piecing these histories together with a collective aim of empowering the experiences of those who’ve otherwise been disregarded by MTS’ most prevalent component of their heritage.

-

Dayton Does Policy

Written By Lillian Stockford

Files and files worth of policy.

As a genre of Mansfield Training School documents, policy is a broad one, encapsulating a huge variety of information. Grocery schedules are outlined in one policy next to instructions for how to deal with runaway residents in another. A policy for ordering and caring for new kitchen equipment is next to a policy template letter for informing a family about their loved one’s passing. It is a rollercoaster of a box in the Connecticut State Library archives. The mundanity of every day in the institution, the moments of fun and community, and the callous and cruel treatment the residents were subjected to–these are all nested in the many pages of policy in one CSL archives box. Each policy was signed by Mansfield Training School Superintendent Neil Dayton, who was superintendent from the 1940s to the late 50s. Whether or not he wrote each one, they all gained his stamp of approval. With so many policies, it is clear that Dayton had both a great deal of power and yet, ironically, almost no power at all. Each element of the institution was looked over by Dayton and regulated. There is a policy where Dayton asks that all news releases be approved by him before going to the press. This policy included both written and verbal information. It is clear that Dayton wanted to be involved at all levels and in all aspects of MTS. Such voluminous policies also speak, however, to the complex system that was Mansfield Training School. So many moving pieces. So many lives involved. To have everyone under your control was a nigh impossible task.

Runaways, (as they were called, a specific change away from the word escapees, a word that would cue others into the fact that there may have been something to escape from), were a popular topic of discussion by Dayton. One policy is about whether or not to call the police when a resident escapes and the procedure for notifying the police about a found resident. There is a line stating that “A patient who has earned community placement does not deserve a police record unless the circumstances are unusual,”. It can be gleaned that there was a hierarchy present. Those who could work and benefit the institution, such as those in the laundry or the cottages, were more “deserving” than those who couldn’t. Which then leads to unequal treatment like that seen in the policy above.

The other policies concerning escapees are no less upsetting in their language and rules. One details that those who run away should be “deprived of all entertainments for a period of three months,” and also cut their hair short. A deprivation of freedom as punishment for fleeing their prison and a physical representation of their escape attempt. In that document, there is no mention of understanding what would lead someone to run away. Clearly, it was a big enough issue to warrant a policy. There is no help mentioned for the escapee to work through what happened to them. In fact, one policy even states that “It is unfortunate that a few boys and girls can make so much trouble and cause many others to be corrected who are not to be blamed, “, a line that clearly blames the escapee for being a “troublemaker”. There is no recognition of the system and institution that led them to flee. Instead, there is only a harsh punishment to strip them of any positives they may have had in their home and to remind them that they do not get to choose. There were even situations where these escapes were not being told to the parents of the escapee. So, Mansfield Training School authorities were not informing families of their child’s deep unhappiness. Or if they were, they were only telling them after the incident had ended. Overall, Dayton’s policy does not seek to address the structural problems that have led to an escape issue but instead seeks to exact further control of its residents, especially those who sought to free themselves from their cage.

Policies covering gifts between residents and employees were another big part of the box, with multiple documents being written on the subject, and with each policy having multiple edits. A level of distance between the worker and the resident was expected at MTS. This distance was mentioned to be for two reasons. The first, and biggest reason, was to prevent favoritism. Even well-meaning relatives simply wishing to thank the caretakers of their family member may accidentally influence a staff member. Or worse off, they may intentionally give a gift to then have footing to ask for a favor down the line. This was the thought process attached to gift giving. Interestingly this portion of the policy evolved over the years. In the beginning, it mainly only concerned aides and other workers working directly with residents. Those “on the ground,” so to speak. However, an edit was made in the early 1950s to include administrative workers and to include not only relatives but also business partners. What connections may have occurred there are unclear for the particular policy document but it does imply that there may have been concerning business connections with MTS.

The second reason given connects back to the previous discussion of escapees. This time it concerns the giving of money to residents rather than the receiving of it. Those who gave money to residents who then went on to escape could be considered as aiding that escape. This sort of warning would have achieved two goals. One, it would have prevented almost all gift-giving, as it would have scared aides who would worry they would accidentally be an accomplice. It would also give an avenue to have a scapegoat if a resident escaped. It wasn’t a structural issue, no, it was simply that a staff member gave them money. That is why they ran away. Pushing the blame on a specific person is easier than confronting the system.

Hundreds of policies dealing with hundreds of aspects of the institution. Dayton’s era of detailed policy tells us both so much and so little. His policy-making answers questions while at the same time posing so many more. Behind each policy and rule is usually a reason, a story, and sometimes even a tragedy. These “reasons behind” the policy start to peek through when looking through enough policies, such as the tragic death of a resident who was given unauthorized medicine that led to his passing. The policies offer a glimpse into these sorts of tragic and preventable events, while also showing just the day-to-day happenings of Mansfield Training School.

-

MEMORIES MATTER… RIGHT?

Written by Paula Mock

Three duplicated photographs of a man and a woman on a gray table, their faces have been blurred for privacy. For me, the team’s visit to the remaining buildings of the Mansfield Training School was sobering. All of the papers that we’d been seeing in the archival library were now brought to life in front of us, making it much easier to visualize and put the pieces together in a physical space. I certainly underestimated how emotionally involved I would get when exploring the site, and how much weight the space seems to carry–you feel a heaviness in each room, especially knowing the long history that has happened here. I think that being together in person, seeing buildings we’d mostly only ever seen on maps, encouraged our collective curiosity and drove us to investigate deeper than we might have if we went individually.

As Jess opens the door that leads to the un-renovated half of the former Longley School, we all crowd around, trying to peer into the vastly different space from the fairly-well-maintained transportation center. UConn occupies half of the building, using the space as a set of offices and labs in an area of campus that isn’t very frequently traveled. Walking down the hallway as a larger group earns us some odd looks from figures in lab coats, but no one approaches us with any questions or warnings, and we swing open the propped-open door. It’s dark, dusty, and honestly pretty intimidating; but, as there’s no signage warning us to stay out, Jess takes several steps forward into the space. I remember a distinct moment where the rest of us held back for a second, thinking, Are we really doing this?

As we walk in and begin looking around, I see something that lingers with me long after we leave the site for the day. Tucked behind a binder in a rusting filing cabinet, a paper folder that holds a left-behind set of photos proudly states, “Memories Matter!”

In the pictures, two young people are smiling at the camera, posing in front of a (somewhat dated) wall, with one person’s arm thrown over the other’s shoulder.

It feels a bit odd to encounter here, where everything is coated in a thin layer of dust and grit, and where every time you pick something up you inhale a number of particles of who-knows-what.

Who are these people, and why were their photos left behind in the abandoned half of the former Longley School? Did they have any connection to the Mansfield Training School? Were they UConn students? What is their relation to each other? Where were the photos taken? And–the big question that has been eating at me ever since we left the school–why were these photos put in an otherwise empty drawer directly behind a binder full of (clearly quickly and rashly abandoned) plans to renovate the Longley Building?

From these questions, more questions arise–which has become a very familiar occurrence while working on this project. Each new thing we discover begins to bleed over into the last, making clearly defined categories extremely difficult and organizing all that we stumble upon nearly impossible.

In my mind, the irony of the phrase “Memories Matter” printed on this forgotten packet of pictures wholly sums up the history of MTS and how it’s been represented & remembered thus far. As with many histories of disability, MTS’s story has been largely ignored and smoothed over in order to lessen the social repercussions or blowback that might have erupted if the public was more aware. Training schools and other institutions like them, as prevalent as they were in the 20th century for “first-rate” treatment of developmental disabilities, have been glossed over in our history books, if mentioned at all. We as a collective have a tendency to conveniently leave out the less “pretty” parts of our histories; if we erase our mistakes, they can’t possibly be repeated, right?

-

In the Archives…

Written by Lillian Stockford

I have toured archives before, as I had taken a course on the university archives. So I went in with some knowledge of how they functioned. As a history major who hopes to enter the field of archives, the “archives” portion of the work was one aspect of the project that drew me in immensely. It was incredibly exciting and impressive to experience the state archives and learn about how they work.

Getting the chance to go back into the stacks was absolutely fascinating as it gave me the chance to learn even more about the field that I love. Seeing the different storage types, such as laying a photo poster board flat in special cabinetry, was very intriguing. The photos especially were interesting as it was a different media type than we had been looking at previously. These boards were set in a specific manner by those at the Mansfield Training School. It was also just striking to think about the difference in the ways they were stored at the campus versus in the archives. In one they were left to disintegrate, likely in a basement. Some of the pictures were missing and in general, the boards had clearly seen some wear and tear. But here, at the state archives, they had been preserved so diligently in a climate-controlled space in a special holder. It was also interesting hearing how archivists go into sites to recover materials, as the fieldwork aspect of the job was not something I knew a great deal about. As someone who is interested in entering the archival field it opened my eyes to the many aspects of an archive. I knew of those who catalouged, preserved, built collections, talked with donors, but I hadn’t considered how they recovered documents that hadn’t been stored in a collection. It also made me consider some of the dangers archivists have to face when doing these recovery missions, like asbestos exposure.

It was also interesting hearing about the laws that affect archives and how that pertained to our project. Privacy laws and their far reach are not something I had previously looked into but they have played such a large role in this project. During this trip I heard about the archivists side, having to discuss with lawmakers how to both protect those mentioned in documents without having to over-restrict. I also saw its myself as a researcher as we had many boxes shut to us for privacy reasons. It was facet of research I hadn’t considered, and it was element of archival work that I knew of but hadn’t fully understood.

It was also fun learning the little tips and tricks of archival research. For instance, putting the rulers in the boxes to save one’s place. These are all aspects of being a researcher that I have gotten the chance to learn hands-on.

-

Cross-Institutional Collaborations: UConn President Babbidge’s 50th Anniversary Address to Mansfield Training School

Written by Jess Gallagher

October of 1967 marks a critical year in the alliance between Mansfield Training School (MTS) and the University of Connecticut (UConn). Dubbed as “A Salute to the University’s 50-year-old Partner,” President Homer Babbidge of the University of Connecticut gave an address at Mansfield’s 50th Anniversary Dinner expressing his gratitude for the University’s association with MTS.

While Babbidge’s work with MTS spanned only five years at this time, in his tribute he mentions the legacy of the “many pioneering leaders who launched this School and nursed it through its formative years” (“Bulletin on Training for Research in the Field of MR”). These leaders include one of the institution’s first physicians, Dr. LaMoure; former superintendent, Neil Dayton; and present-day leaders such as Governor John Dempsey and Superintendent Francis Kelley—whom he affectionately calls “Fran.”

Importantly ,Babbidge’s thoughts and praise for MTS greatly relied on the key connections between UConn’s research with residents from its Psychology, Education, Speech, Psychical Education, and Child Development departments/programs. With these UConn departments and research programs serving as the main catalyst for the relationship between the two institutions, Babbidge claims:

“If fact, they [the researchers] deserve accolades for their partnership they have developed between our two institutions—a partnership that may one day make this little community of Mansfield into one of the world’s greatest centers for the study and treatment—and yes, prayerfully, even for the prevention [of intellectual disabilities].”

Babbidge continues, recalling societal attitudes surrounding the topic of intellectual and developmental disability just a few years prior to his speech as being “locked behind the doors of late-Victorian propriety when those few who cared had to work with..in the dank atmosphere of ignorance and among the cobwebs of rejections” (“Bulletin on Training for Research in the Field of MR”). What is the most interesting piece of rhetoric here is the insinuation that within the walls of MTS residents still weren’t confined. Yet it’s clear that restraint logs, reports of abuse regarding the distribution of psychotropic medicine, and newspaper articles detailing the physical abuse that went on at MTS during the time of this speech and the years that followed were realities.

Babbidge’s choice of the words “community” and “partnership” from the quote above also prompts us to question how those within positions of power at MTS and outside of it viewed these ideals as a whole.

For Babbidge and many researchers within the field of science, medicine, and psychology, community/partnership goes hand-in-hand with study/treatment. We can assume, based on the context of the time, that ‘attitudes’ toward disability that Babbidge picks up on, and lack of leadership from disabled people on services related to disability due to ableism and disablism that ‘community’ was not fully designed for the true benefit of the residents at MTS. Community and partnership, instead, relied on the mutual gain of researchers and the institutions themselves whether it was financially, academically, or socially. Becoming the “greatest center for study and treatment” through an MTS-UConn partnership would not only boost the elitism of UConn and its standing as a top-rank research institution for its scientific discoveries but attract the attention of other funders such as NIH for the research of faculty members.

“Community” at MTS relied heavily on the act of othering—an act heavily reliant on the power dynamics between administrators, staff members, researchers, and residents. In countless fields of research, people with disabilities are often seen as the “objects” of study by researchers. MTS residents would be dehumanized simply through their position in the eyes of researchers and some staffers.

Babbidge’s critique of the social attitudes of the time doesn’t stop there. Toward the end of his address to the many parents, scholars, administrators, and audience at this anniversary dinner—Babbidge paints an image of what life was like prior to the work of MTS-UConn and a resurgence of new “progressive” discussions surrounding disability.

“The deaf, the blind, the mentally ill, all suffered at the hands of a society that would rather lock up its problems in an institution than do something about them. And somehow we managed to break out of the darkness. Brave parents, long tortured by the ignorant slings and hostile arrows of society, brought their afflicted children—almost literally—out into the daylight. By the single simple act of acknowledging [disability] as a problem they “opened up the doors and let the sunshine in.”

This is a very triumphant narrative from Babbidge, but his language is especially interesting. Here, he moves to saying “we” within his speech, saying “we managed to break out of the darkness.” But who is this “we?”

In the next lines following this quoted material he’s specifically talking about the parents of residents from MTS and the wider collective of parents of disabled children and adults, not disabled people themselves—but this phrase becomes complicated when we realize Babbidge’s own experiences with disability. In a Hartford Courant article, “Babbidge Dies; Former UConn President Was Author, Collector,” William Cockerham writes, “Babbidge also had a handicap. When he was a child, he was looking out of a bedroom window at some older children playing ball when the ball came through the glass, destroying the vision in his left eye.” How does Babbidge’s relationship to disability work with his status as University President? And most especially, in his connection to the Mansfield Training School during these years – where some residents were also identified as “blind” along with “mentally defective.”

There have yet to be any specific narratives from Babbidge himself discussing his relationship to disability, but historically, Babbidge was a key figure in Deaf history and “The Babbidge Report” to Congress on the “dismal failure” of oralism. In an article from Gallaudet Press, the findings of the Babbidge report “coupled with the Vocational Education Act Amendments of vocational rehabilitation funding of postsecondary deaf and hard of hearing students during the 1960s, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (equal access to communication, interpreter training), PL 94-142 (Education for All Handicapped Children Act of 1975), and now the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act of 1990 (IDEA) all contributed to the expanded changes in educational options for deaf and hard of hearing youngsters of public school age.”

With such a large role in both Deaf history and in the history at MTS—Babbidge’s position as being both frustrated and angered by society’s current treatment of people with disabilities makes sense. For him, and many other parents at MTS, the institution itself was viewed as “progressive,” yet, still continued to use deficit-based language and curative models when addressing disability, in practice, conversations, public relations, etc.

While parent advocacy played an important role in advocacy, the image offered by Babbidge of these parents being tortured by society’s ideals contributes to language that we see as being harmful today that de-centers disabled people in advocacy movements. Babbidge continues this thread by saying:

“The dark days of ignorance and indifference are behind us; we have moved out of backward old fashioned institutionalization into the mainstream of community life. We have public support. We have enlightened vigorous leadership. We have a University nearby that wants to help. All systems are go.“

The cycle of institutionalization continues to persist through mass incarceration, “smaller” institutions, and many other ‘fixes’ that have been used to address institutionalization of the 20th century. The days of ignorance have never truly been behind us; it’s still currently with us, and in front of us. As medical, social, policy, governmental, political, justice, and rights-based conversations surrounding disability continue to change, shift, grow, and develop–we are bound to see even earlier versions of advocacy and the language we grow as “outdated.” Understanding this history, in turn, can help better inform our present, and engage us with new models, ideas, and narratives for the future. -

No Private Spaces

Written by Lillian Stockford

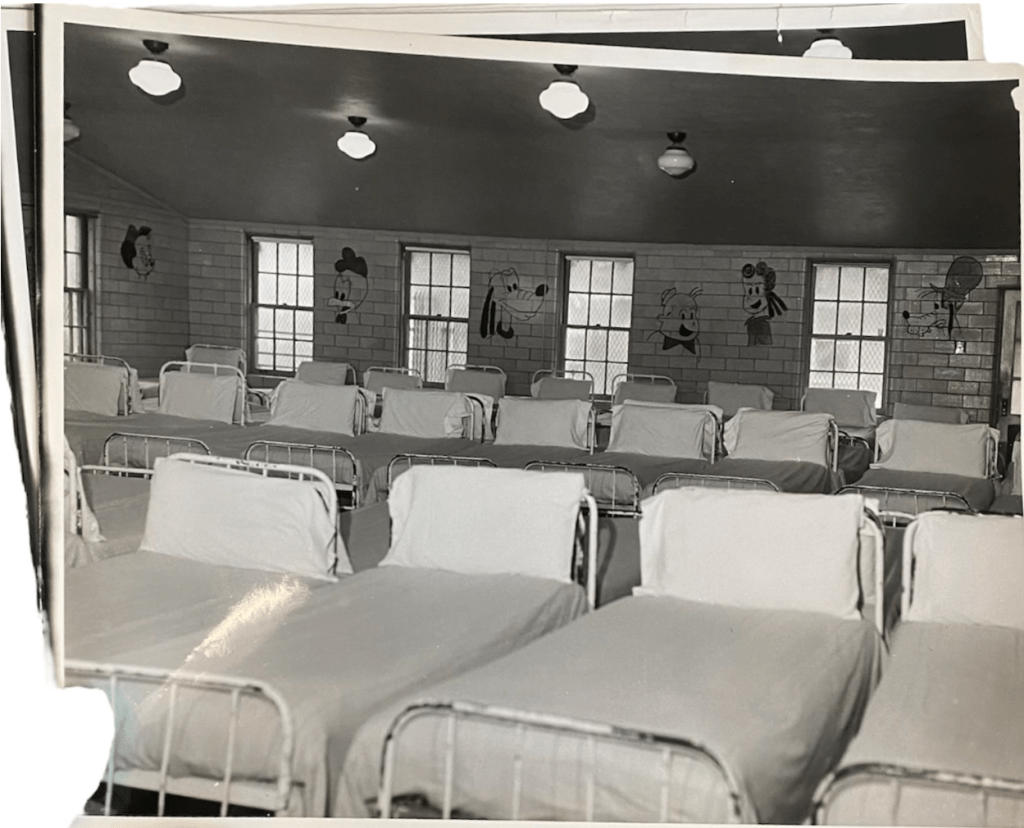

Visual Description: A photo of the children’s dorms. There are twin-sized beds on metal frames very close together, an estimated 6 inches to a foot apart. The beds all have the same bedding. The walls are painted bricks. There are small children’s character-themed murals on the walls, such as Goofy and Donald Duck. The taking away of one’s privacy is in many ways dehumanizing. It removes a person’s freedom and creates an environment where it is a struggle to truly be an individual.

Looking at the Mansfield Training School dorms, a few descriptors come to mind. A minimum security prison. A place stripped bare of personalization. Sterile and unwelcoming.

The image of the children’s dorms is especially damning. The beds are so close together that they almost form one continuous bunk. The lack of privacy and personal effects. One may argue that it was for resident safety. However safety does not have to mean inhumane. Not giving residents any space to have as their own does not make them safer, it simply takes away a basic human need. It exposes the insidious belief that people with disabilities do not need or deserve privacy. And this belief further leads to a lack of respect and understanding.

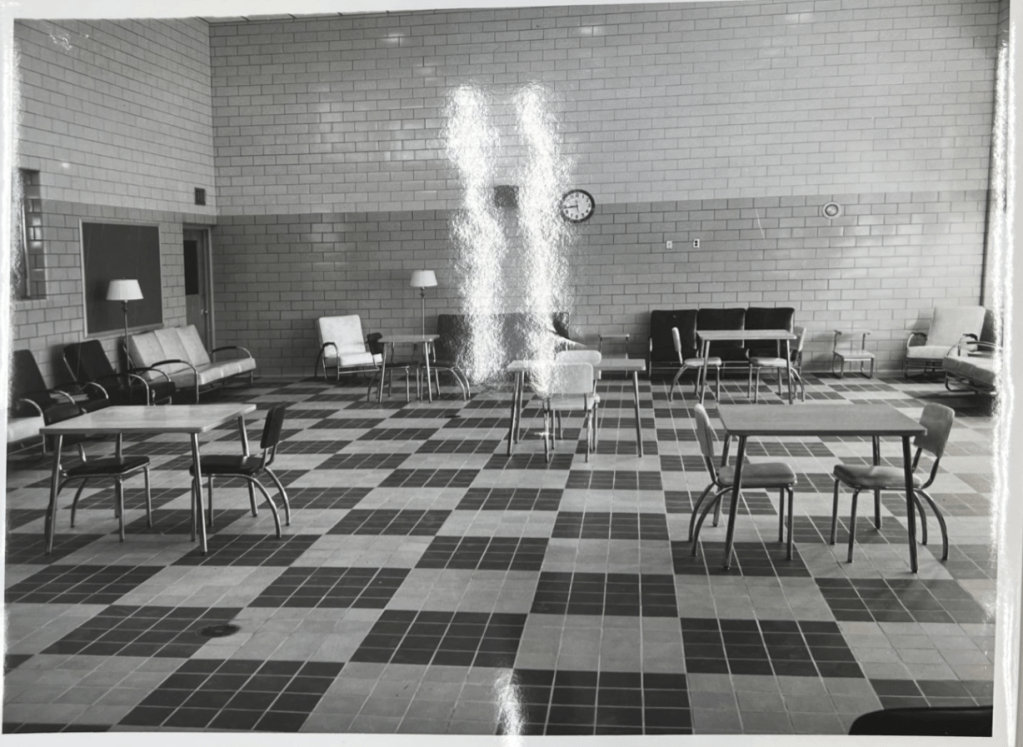

Even in spaces meant to be “homey” there is a cold feeling. The decals of cartoon animals on the walls of the children’s dorm do not do much to brighten the space. If anything they make the space feel more empty as they make the deficits of the room more obvious. There was a “day room” to function as a lounge space for residents but it was also depressingly bare: empty tile floors, minimal furniture, and naked walls come together to make a less-than-comforting environment. It feels almost clinical, like a doctor’s office waiting room. The “day room,” much like the dorm room, lacks warmth and a feeling that this is a home. The institution may have handled medical matters but it also was a place of living for over a thousand people at its peak and it is clear that making the institution a comfortable home was not valued by the administration.

The day room of Merritt Hall in the 1950s. It has a black and white checkered floor and painted brick or cinderblock walls. The visible walls are bare save for a clock and a small blackboard. The furniture is concentrated on the edges of the room. There are three tables scattered in the middle of the room, each with two chairs. It is also interesting considering the largeness of the superintendent’s home. It has pillars, a feature that tends to be associated with power and wealth, but the residents can’t have two feet of space between the beds? Can’t have stall doors in the bathroom? When placed side by side it is disturbing to see the differences. MTS was a home for its residents. Many didn’t have the option to go anywhere else if they found their lodgings less than satisfactory. For those who had entered the institution as young children or toddlers, MTS was the only home they had ever really known. For those unequipped by the system with the tools to leave, there were not many options available. For children, even less so, as some were wards of the state and given no choice concerning where they lived. Some residents had medical needs that stopped them from leaving, as the resources were not available outside the institution. They were living in a system that pushed them towards institutionalization and then failed to support them once they were admitted. A system that did not value choice and freedom.

It speaks to a larger trend of not viewing residents as people with feelings and preferences.

It also makes one wonder why it was necessary to have the beds so close together. Was it simply a lack of care? Or does it allude to a larger systemic issue of overcrowding? Not all of the dorms had this sort of layout, though the others were not objectively good, which I will come back to later. If a facility has to have this sort of layout in order to fit the number of people they need to then there is inherently a structural issue. This sort of design should not have been considered a norm but rather a failure.

A photo of the Merritt Dorm in 1956. The floor is tiled and the walls are painted brick. There is a drain visible on the floor. There are short walls organized in a cubicle- formation. There are no doors to the cubicles. In each cubicle, there are three beds to a “wall”, with a nightstand and a chair dividing them. The chair is in front of the nightstand. This is a picture of a dorm called the Merritt Dorm, from 1956 which is better than the children’s dorm, with at least wall structures present, but it is still not adequate. Better than nothing is still not good. There is still a complete lack of privacy, just assuaged a bit by the cubicle-style walls. It still does not look like a home or even a dorm—still no privacy, a feeling of overcrowdedness, and blank walls.

Even with improvements, the systemic issues within institutions still leak in. Even the newer, better option does not fix the issue, merely putting a bandaid on it. There is a lack of respect for residents, for their needs, for their wants, and for their space. Especially if you consider the length of time that people were living in the institution. It was generally not as short as a hospital stay. People were entering the institution as young children and then not leaving, living in these dorms for decades upon decades. It is also important to consider the accessibility of these dorm setups. The tight spaces would not have worked well for residents who use wheelchairs or other mobility devices. The dorms allude to a larger trend with the institution of not considering the comfort of residents. Of not giving them the freedoms they would otherwise have been afforded. They demonstrate the systemic failures of the institution and a lack of respect for the people who lived there.

-

Why I’m Here-Ashten

Hello! My name is Ashten 🙂

I first heard about Mansfield Training School through other students. Mostly whisperings about “haunting.” I was already deeply interested in the history of deinstitutionalization and Disability Studies. I couldn’t get the thought of MTS out of my head. Especially as a UConn student, the erasure of Mansfield Training School’s history was hard to grapple with. I had been to the site and paid my respects, but I felt like a proper acknowledgement of the site was needed.

That next semester, I was taking Brenda’s course on Disability in American Literature and Culture. During one of the classes, Jess and Brenda presented the work they had done on the Mansfield Training School Project. I was so overcome with appreciation that there were people out there working on a project like this. I knew that I had to try to learn all that I could about the project. Luckily, I was able to join an amazing team of researchers to continue the project.

I feel an obligation to honor the residents of MTS and those impacted by its legacy. The history of institutionalization in this country is egregious. It is so ingrained in our society that one has to make a conscious effort to understand and dissect the role it has played for so long and the power structures that enable it, and continue to perpetuate carceral modalities of “care.” As a kid and teenager, I was institutionalized. I will never forget how much the pain that has caused me and how it continues to impact me today. As a result, I was unsure if I would have the opportunity to attend college. Now that the university I am attending is so closely tied with institutionalization, I cannot ignore it. I will never understand what it was like to be a resident at MTS, but I do understand the importance of helping the stories be told. I am so lucky that I get to work alongside such an amazing, thoughtful, and dedicated group of people on this project. I am hopeful for the education, conversations, and change that this project will bring.

-

Why I’m Here-Madison

Hi, I’m Madison!

To be frank, I had no idea what disability studies was until I met Brenda. I knew people who were disabled, that people struggle with disability, and that there were probably some ways that the world could be more accommodating to human beings, but never realized how deep the concept of “disability” runs through everything we do, see, participate in, and so on.

I began working with her (and Ashten, too!) when I became a moderator for the Disability & Access Collective Blog, aiming to elevate community voices and prompt discussions about accessibility on and off of the UConn campus. When I learned that Brenda was looking for students to join her and Jess’ project on MTS, I very quickly and eagerly began my application. Having begun this work surrounding access and disability on the UConn campus through the DAC blog, I became fascinated with how UConn might be tied to the greater legacies of institutionalization that shapes the current landscape and discourse today.

I am so grateful to be working on this project with such an amazing group of people, and hope that this project will empower those who have their own stories about Mansfield to voice their experiences. While I feel incredibly lucky to have been given the opportunity to excavate Mansfield’s history and bring light to what has happened – both inside and outside the walls of the institution – I hope to see the work that we’re doing validate and elucidate the experiences of surviving residents of MTS and their families.

-

Why I’m Here- Ally

Hello, my name is Ally

My interest in disability studies began after I took Disability in American Literature during my junior year at UConn, where I first heard about Mansfield Training School. I originally approached both the class and the legacy of MTS through a sort of detached lens— I was interested in learning more about disability, but disability wasn’t an experience I or the people around me were a part of. As I began to participate in discussions and read more about disability through the perspective of activists and authors like Riva Lehrer or Cece Bell, I realized how my own familial ties to disability had been swept under the rug and purposefully overlooked since I was a child.

I’ve always believed in the power of storytelling to prevent erasure. Disability history, on both an institutional and personal level, continues to be buried by the passage of time. This burial is seen on a macro and micro scale with the lack of history taught in K-12 schools as well as the family stories of disability not being discussed at home. The only way we can prevent people and their experiences from being forgotten is to tell their story in full, the best way we can. Our research team has spent hours at the archives, pouring over documents left behind at the Mansfield Training School (MTS), but our job is just one piece of the complex puzzle. I hope the work our research team conducts will shed light on the wrongs done to residents at MTS as well as encourage survivors of institutional abuse to share their stories.

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.