Here, we’ll walk through the history of the UConn-MTS partnership and important points from 1963 to 1993 that shaped MTS. We’ll also begin to explore how UConn’s involvement with the institution contributes to both its flourishing and closing.

1963

Bonds and Ties that Last a Lifetime…

1963 marked the beginning of the MTS-UConn alliance. In this year, MTS began to garner the attention of a young Homer Babbidge, President of the University of Connecticut, and the community. In a newspaper article by Betty Palaima, titled, “Mansfield-UConn Ties Need Further Binding,” the Mansfield community begins to see how the work between these two institutions becomes more and more interwoven. In setting the scene, Palaima describes MTS as a 1900 bed institution with 1,100 acres of land. For many of the children at MTS, they accepted based on medical referral and voluntary admissions who have disorders such as “brain-damaged, epileptic, autistic, or dysphasic.”

Whether playing local high schools in football games, hosting dances, or going on outings such as picnics—MTS relied heavily on the volunteers from UConn in order to keep their recreational programs running. Aside from playing sports, the vocational program at MTS also provided UConn with multiple maintenance workers from the teenage residents at MTS. For the Superintendent and trustee members at MTS they make it clear and well known that “The boys and girls at Mansfield are available for landscaping, gardening, house cleaning, and ironing” and then go about adding a phone number if readers would like to check out the availability for these workers (Palaima 2).

In a short introduction, Kelley proposes that the people of MTS need companionship and people who can come in and spend time with these residents. Thus, the birth of a student companion program is born. The match between UConn and MTS as a partnership between two schools is then born from the mutual need for volunteers and close proximity. While the intention was to provide care and kinship, other members of the UConn community began to quickly become involved in MTS for other reasons. Some of these members include: Professor Alvin Liberman, David Zeaman, and Sam Wytrol of the Psychology department; Eleanor Lucky of the Child Development and Family relations department; Ingeborg MacKellar of the Foods and Nutrition department; Thomas Mahan and John Tenney of the Education department; Earl newcomer of the Botany department; Raymond Pichey of the Social Work department; Gene Powers of the Speech department; Frances Tappan of the Physical Therapy department; George Van Bibber of the Physical Education department; and many other faculty members. In order to garner more volunteers, Kelley announces that many of the young teenage girls would also appreciate guidance from UConn’s female students on things such as personal care and homemaking. And with that, MTS opens itself up to UConn students for tours and visitations upon scheduling with them ahead of time. This article is one of the first public calls that UConn will receive and reciprocate from MTS, as future planning and work with the institution reveal many ways UConn can profit from their research and work with disabled identities.

Wallace Moreland, assistant to President Babbidge, spent a majority of his time writing and receiving letters from various offices across the state of Connecticut. From MTS to the Office of Public Relations, his responsibilities involved growing UConn’s research opportunities by serving as a critical pinpoint of contact. On November 11th 1963, Moreland, sitting in his office, received a letter from John F. McDonald from the Office of Public Relations. In regards to the ‘Mental Retardation Facilities Construction Act,’ Moreland receives an update from the formerly proposed bill. In a newly passed bill called Public Law 88-164, it covers the “(i) construction of research centers and facilities, (ii) construction of community mental health centers, and (iii) training of teachers of handicapped children.” With a net total of $295 million ($2,735,170,588.24 today) being funded across a three year period for adherence to these terms, we wonder why Moreland had been addressed in this letter as the bonds between MTS and UConn are just beginning to form. The further breakdown of this bill explains that in part (i) $20 million ($185,435,294.12 today) would be used to cover building costs while the remaining funds should be used by the institution to cover human development. Part (ii) would be targeted specifically at colleges and universities to encourage the development of clinical facilities (both inpatient and outpatient) which would provide $22.5 million ($208,614,705.88 today) over the span of three years to aid in the research, diagnosis, treatment, education, and care.

This legislation suggests that this money from the government be used to develop medical schools and affiliated hospitals—but that it could also be granted to ‘such other part’ of a college or university. Aside for the millions already available, part (iii) provided $67.5 million ($625,844,117.65 today) for custodial care facilities and an additional $45.5 million ($421,865,294.12 today) for the training of teachers at UConn through fellowships or traineeships through “assistance to such institutions to make such training possible…this portion also expands the areas of assistance to all handicapped children such as deaf, speech impaired, visually handicapped and emotionally disturbed” (John F, McDonald to Wallace Moreland, 11 November 1963). As a further incentive, an additional $2 million ($18,543,529.41 today) would be provided for the demonstration of projects at the educational and research institutions. In working with MTS, UConn would not only be able to establish their medical school, but provide extra funding for any research conducted at MTS as their hospital and campus continues to grow. Without MTS and its partnership, it seems that UConn would not have been able to become the highly respected research institution that it seemingly is today. The bill’s newest addition of title (iii) would make working with an institution such as MTS a much more profitable experience for faculty members and administrators at UConn.

And thus, perhaps coincidentally or through the funding detailed to Mr. Moreland in 1963, UConn Health—a medical school with an affiliated hospital—was born in 1966.

1964 and 1965

Grants, on Grants, on Grants for the University of Connecticut

With an uptake in grants and support through the University of Connecticut, MTS was able to hire a total of 943 staff members across full-time, intermittent, and part time positions. During October of 1964, with newfound assistant through MTS’s partnership with MTS, the Physical Therapy Department instituted a close partnership with UConn’s School of Physical Therapy that would help “orient students to the problems and treatment of the [disabled], and furnishing patients for practical training sessions” (Annual Report, 1964-65). This partnership resulted in 230 students from UConn visiting MTS to conduct field work during this year. On the note of working with UConn, MTS reports significant progress this year in regard to their affiliation with the University of Connecticut with the help of legislative funding under the Public Law 88-164, the same law that provided UConn the funds to build their medical school. Under this law, MTS received $600,000 ($5,491,277.42 today) toward the construction of a Rehabilitation, Diagnostic, and Administrative facility at Mansfield. With these new funds and the support of Law 88-164, the university became increasingly more interested in the experimental prospects of Mansfield Training School and the extra funding this research could bring.

In the 1964 and 1965 fiscal year, the University’s Department of Psychology received $51,575 from a NIMH grant to support Professor David Zeaman’s research in experimental psychology at MTS, which does not include the additional $31,465 from a NICHD grant to support a doctoral training program under the direction of Professor Samuel Witryol. Dr. Zeaman also received an additional $24,000 from NICD to study the physiological aspect of learning by studying the eye movements of residents at MTS. NIMH continued to fund $25,000 for in-service training of attendant personnel from UConn’s School of Social Work. Outside of the field of Psychology, a total of $10,900 was provided by the Kennedy Foundation for Physical Education and Special Education. A combined total of scholarships received by UConn from their partnership with MTS led to $132,040 in research funding, which equals to around $1,208,447.12 today.

The University of Connecticut used four categories to establish themselves as a prominent research giant and notable university. While working with people at MTS for research purposes, UConn also showed that the residents of MTS “were employable” by training 15 boys from MTS to work it its cafeteria and Student Union building. This employment, viewed as a ‘pilot project,’ gave MTS an additional grant from the U.S. Department of Labor of $500,000 to train 400 residents between the ages of 16 and 35. In the following years, the MTS-UConn evolved into a joint seminar series. This bi-monthly series of interdisciplinary postgraduate conferences featured world leaders in the field and hosted over 200 students, faculty, and staff members from across CT. The students at UConn were so inspired by these talks that the class of ’68 resolved to make MTS their humanitarian responsibility. By hosting weekly activities, 350 students also brought along UConn’s mascot, Jonathan VII to the 1,800 residents of MTS.

While the ‘goal’ of many of the programs at MTS during this time centered on “attitudes holistic with the view to fully developing the total individual,” it seems that the 1,950 residents at MTS were often used for the benefit of the institutions they inhabited. At this time, the school’s maximum capacity of 1,700 was more than exceeded. Overcrowding, ill-treatment and attitudes towards residents, and generally restrictive living practices left MTS in a similar state before their funding. However, with the support of the University of Connecticut, MTS was able to show the Mansfield community and its families all the ‘good’ that came out of their partnership as a guise to the horrid conditions.

As students became more and more excited to work with participants, the students of the Home Economic Club began to sponsor a ‘Good Grooming’ class, cooking classes, sewing classes, and other homemaking classes at the Longley School. A break from the overcrowding and abuse by staff, many of the girls who worked with UConn students would be able to participate in activities with other girls that were often not available to them at MTS.

Outside of UConn, and back within the walls of MTS, the Board of Trustees at MTS note a recurring issue they see across the institution—this being the state of Knight Hospital and the entire MTS campus. While the State of Connecticut is capable of providing more than adequate funding for the expansion of UConn, it seems they are more hesitant to assist the current operations of MTS.

The existing 85 buildings at the Mansfield Training School are in a state of disarray and disrepair. The years of 1964 and 1965 showed a significant growth in programs, yet, the physical space of the institution itself could not uphold them. A plea to the Governor of CT in their annual reports, MTS noted that around 10 of their current buildings did not have access to hot water and relied solely on individual systems for power. The transitional dorms also used to curb overcrowding were slowly becoming more and more necessary as the population grew. The staff continued to note that much of the shop equipment they did have were inadequate to keep up with modern building equipment and facilities. However, the most critical part of MTS being Knight Hospital, where a majority of residents are treated, was unrenovated and unable to meet modern standards of care. Its lack of compliance with fire codes, and lack of intensive care facilities have greatly affected the people at MTS. The request to renovate was unfortunately not approved under the 1964-65 Legislative body, so the building continued to remain unsafe and overpopulated.

Despite this lack of funding for Knight Hospital, UConn and MTS took advantage of the funding provided through Public Law 88-164 to start their plans for the construction of a new Diagnostic Center. In a meeting with Dean Hugh Clark, Dr. Zeaman, and Superintendent Kelley, in September of 1964 the team planned to contact faculty members at UConn to explore the advantages of constructing a university affiliated research facility at MTS. Now, the reasoning behind building this facility on the grounds of MTS was sorted out between these members quickly. It seems that in order to thoroughly study the 1,950 adults and children at MTS, a center should be established on the grounds to have easy access to the diverse ‘representative groups’ of many disabilities. So, the reason MTS was targeted as a prime space for this institution was because of the variety of disabilities, bodies, and identities that this population held.

On January 15th of 1965, Francis Kelley drafted a proposed sketch of the Diagnostic facility to President Babbidge in his freezing office at MTS. On this chilly winter day, Kelley drafted the measurements and schematics for the proposed building that could potentially fund MTS for years to come. The building itself would be large enough to house services such as Medical, Psychological, Residential Care, Social Service, Rehabilitation, Administrative, and Research Services. Inside the building there would be a clinic and multiple medical examination rooms for residents who were being examined by University professors and doctors; a medical records room to house the countless files from 1,950 residents; a medical library; child’s clinic; physical therapy unit; conference rooms; hydrotherapy tubs; Social Service Offices; and Psychology offices that would include interviewing rooms, play area, and research laboratory. The justification for the building still reads as the following:

“At the present time, some 19 departments from the University have become interested in […] and are using the Training School facilities and residents in their research and training. Some of the more active programs are Psychology, Education, Home Economics, Child development, Physical Therapy, Social Services, Physical Education, and Speech and Hearing. As a result of this growing affiliation, the University has requested space to expand the cooperative program […] and to accommodate experimental research. A committee of University faculty has indicated a definite need , on the Mansfield Training School grounds for a laboratory classroom; psychology interviewing rooms; observation rooms with one-way vision…Recent federal legislation passed by Congress regarding [intellectual and developmental disability] makes federal funds available on matching fund basis under Public Act 88-164.”

(Francis P. Kelley to Wallace Moreland, 15 January 1965)

With MTS being denied funds to work on their already established buildings, it seems that partnering with UConn may have been the only way to receive any funds at all for their buildings. The pressure of overcrowding and inability to modernize buildings most likely left MTS searching for ways in which they could pull funds from this act. Perhaps, a reason behind the overcrowding at MTS did not solely exist because of the institution’s willingness to accept whoever stumbled across their halls. Instead, it seems the population and diversity of disabilities is what attracted UConn to MTS. Maybe there was added pressure to accept people with various disabilities as a way to push forward psychological and medical research? These are questions we cannot answer based on past documents. We were not present in the rooms where the people of MTS were being discussed, nor do we know Babbidge’s or Kelley’s intentions.

All we can gather is that on January 22nd 1965, Babbidge wrote a personal letter to Governor John Dempsey advocating for the establishment of the Diagnostic and Rehabilitation Building at the Mansfield Training School and how it would prove to be a real boost to University staff. Twelve months after this plea, on December 23rd, a letter was drafted as an agreement to Governor Dempsey by Babbidge and Kelley. This agreement reflected the decision of both Babbidge and UConn’s Board of Trustees along with Kelley and MTS’s Board of Trustees, to jointly staff and operate a diagnostic center on the grounds of MTS with support from the Public Law 88-164, under Title I. The policies of the center will be determined by a committee that will consist of three members from UConn and three from the department of health.

1966

Goodbye Mansfield Training School, Hello UConn Health

Oddly enough, with consistent talk and resolution to establish this diagnostic center, in January of 1966 Kelley received a rather odd letter from Babbidge. Babbidge’s once strong convictions in creating a joint diagnostic center seemed to have completely changed in a year. In a letter affectionately addressed to ‘Fran,’ Babbidge remarks that he hopes MTS and UConn can continue their impressive partnership that possibly features UConn’s medical school. Babbidge then offers Kelley a few items he would like to consider saying that the concept of a semi-autonomous center that was jointly administered would not work satisfactorily. He deemed that the operation and ownership of such a center would not be ‘appropriate’ for UConn. The only realistic possibility would be to have MTS own and manage the physical facility while UConn staff would accommodate by invitation.

The second piece of consideration: Though the Department of Pediatrics in the School of Medicine would be interested in the ‘problems of MR’ it would be unrealistic to expect them to center their work outside of Farmington and UConn Health. Mansfield could never create diagnostic resources equal to those anticipated at Farmington, so why try? Though MTS, in Babbidge’s words, “should be designed to maximize the interests of our Storrs-based talent, including appropriately augmented staff in fields like human genetics…this may diminish the chances of getting a federal grant” (Homer Babbidge to Francis P. Kelley, 4 January 1966). And so, the intentions of UConn and Babbidge were revealed through this letter of correspondence to Kelley. At this stage in their development, MTS would never be able to support a diagnostic center. Unlike UConn, they were not given the funds to build a medical school or hospital. With the rise of UConn Health came the beginning of the end of MTS. After providing MTS with staff and other resources, they were once again stripped away when a more profitable and desirable project emerged. As the late 60s came to a close, the horrors of what happened behind the walls of MTS also became more apparent. Residents now being required to make their clothes, overcrowding and failed health exams, and growing distance from UConn caused MTS to reach a breaking point.

1967

MTS Gets “HIP”

With the potential development of a newly formed center, staffed with the assistance of UConn, MTS experienced a short period of rapid growth and opportunities. With the backing of UConn, funding from research organizations and the government, and exposure of now being one of the country’s leading institutions for disabled people—MTS was gaining more and more attention as well as opportunities.

From the years 1964 to 1969, MTS was able to establish the ‘Hospital Improvement Program’ as a way to make sure each of their residents receives proper care and education around self-grooming, Supported by federal funds from the Hospital Improvement Program grant, the program funded MTS with just five years of support to concentrate on older age groups with an emphasis on self-care skills. The grant itself did not change the structure of MTS, instead, it made aides work with residents one-on-one in dormitories. Some of the activities both aides and residents participated in were feeding training, toilet training, dressing, personal hygiene, and good grooming. Though aides aimed to provide individualized care, a large part of the HIP focused on modifying behavior and ‘improving discipline’ (“Hospital Improvement Program Progress Report,” 1964-1969). What this meant was that when aides deemed a behavior inappropriate, they were encouraged to change said behavior by utilizing restraints. The goal of this ‘tactic’ may have been to modify behavior and, while HIP nurses tried to limit restraint use, restraint logs from these years are nonexistent. However, MTS credits its decrease in population and overcrowding to the support of the HIP program as the population in 1967 has decreased to 1,747. Due to its successes, the HIP progress report announced that MTS will receive another 5 years of funding to continually assist their residents well into the mid-70s.

In an examination conducted by the American Association on Mental Deficiency, MTS’s dormitories were significantly overcrowded, there was a lack of privacy for residents, inadequate hospital services and antique buildings, and an alarmingly insufficient number of employees and qualified professional personnel. With insufficient funding and inadequate staffing, MTS began to see that they could not carry out their operations as they had. The farm and its operations that were once run by residents were now being transferred to UConn. In an agreement drafted on May 29th, 1969, MTS granted exclusive use of their land, buildings, and equipment that were related to farm production to UConn. As part of this deal, UConn was able to construct buildings on the land west and east of Route 32 indefinitely, which would be deemed ‘Parcel 1’ of the agreement.

In ‘Parcel 2’ of this agreement, this land would be used for teaching, agricultural resources, and natural resources, but no buildings shall be erected or demolished. ‘Parcel IV’ would be reserved for MTS camping activities and UConn would be granted use of the land for purposes that do not distract from these activities. Upon agreement, UConn will be responsible for road maintenance and snow removal; purchase electricity to serve the new construction; and will not build on the land without written permission from MTS. With the new agricultural land from MTS, UConn was able to continually grow their university across Mansfield while also being able to profit from farm production on these fields. The land of the MTS campus itself was of value that UConn would be able to benefit from. MTS’s institutional land averaged about $1,912,500 in value ($14,784,927.79 today), while its agricultural land totaled $791,500 ($6,118,834.17 today). Even the woodland areas averaged to at least $52,000 ($401,995.42 today), and the residential land at MTS totaled $166,000 ($1,283,239.08 today). Though the land of MTS was valuable, the buildings themselves and equipment within the institution continued to age as time progressed. The once ‘vibrant’ program that offered countless activities, special programs, and initiatives with the assistance of volunteers from UConn slowly began to die down from 1967 to 1969.

1970s

“Our Residents Celebrate Our Success”: Brutality and Abuse

Content Warning: This section depicts mentions of violence, abuse, and derogatory language used against disabled people.

As life at MTS continued to dwindle, Superintendent Kelley spent some of his time hosting workshops and speaking publicly about the work he’s seen at MTS. At Temple University in 1972, Kelley spoke at the workshop listed above, hosted by the Department of Special Education. In his address, Kelley mentioned that language was the biggest barrier in teaching a disabled person since it was “limited or non-existent” (Stephens, Beth, et al). Other obstacles he would go on to cite were blindness, deafness, cerebral deformities, minimal attention span, and interfering behaviors. Kelley does not go on to further explain these factors. It’s clear that to Kelley and MTS, disability is seen as a deficit. For them, he claims that simple tasks can be monumental, thus, the best way to support these individuals is through small residential units, individual attention, trained staff with a high staff-to-resident ratio, and availability of professional consultation—all of which MTS lacked. To have their residents celebrate their success,’ Kelley claims each resident had goals set for them that they could achieve and that MTS would be “observing every increment of success” (Stephens, Beth, et al). So, the question we can now ask is:

What did success look like to MTS?

On March 17th, 1972, “The Chronicle” publishes an article titled, “MTS aides claim brutality used on retardates.” After speaking to aides at MTS, it was revealed that many of the employees who cared for the 1,500 residents often slapped, kicked, and/or punched the residents. Though the administration attempted to crack down on the brutality, extreme violence was still common in residential care. Kelley denies these claims and says that aides may use ‘poor judgment’ in these instances. He further states that he is confident in the quality of aides at MTS and has never heard of any reported instances of violence since the institution has had no problems finding quality aides. However, this seems contradictory to the history of MTS and its inability to find permanent staffers. In the women’s ward, two aides witness other staff members tying “kids” to chairs and beds for punishment or convenience. Another male aide, who continued to work at MTS mentioned not knowing what to do with the kids so he would often smack them across the hand. While every resident at MTS is referred to as a ‘kid’ regardless of their age, the infantilization by staff members is a consistent theme seen across MTS’s history as an institution. Another aide mentioned that at least 99% of the aides he has seen at MTS have slapped a resident at one point or another. While the administration attempted to crack down on brutality by instructing aides not to restrain or grab residents that would attempt to escape, there were no policies that were set or individuals to oversee this.

In the hierarchy at MTS, older aides often taught new aides their ways of ‘working with the residents.’ While new aides were not trained correctly, older aides taught them how to use brutality as a means of discipline. Among the aides was a culture of silence, one where no one ever reported the abuse of residents, no matter how heinous, for fear that word would spread. If aides did report abuse, they were shunned by other aides and would eventually resign due to how uncomfortable the environment would become. New aides would then evolve into the old system, and the cycle of abuse would continue. During the night, third shift aides would often use restraints on residents without orders as a way to keep watch due to insufficient staffing. If residents misbehaved, they were forced to skip meals. While the aides that were interviewed said they witnessed this brutality occurring two years before this article, one woman cited that people don’t change that quickly and they’re still there.

If a resident had difficulty adjusting to institutional life, they were often physically abused until they complied. And, if questions were raised about bruises, one aide excused it as terminal measles. No one ever questioned them.

While some aides entered MTS with intentions of wanting to help, the environment of MTS was so hierarchal and bent on silence that aides often did nothing. The cruelty of overcrowding, insufficient aid, the lack of activities on the wards, the atmosphere of the prison-like buildings and brutal architecture, and the expectations for care are all factors that contribute to the brutality and abuse at MTS. They were not treated as people.

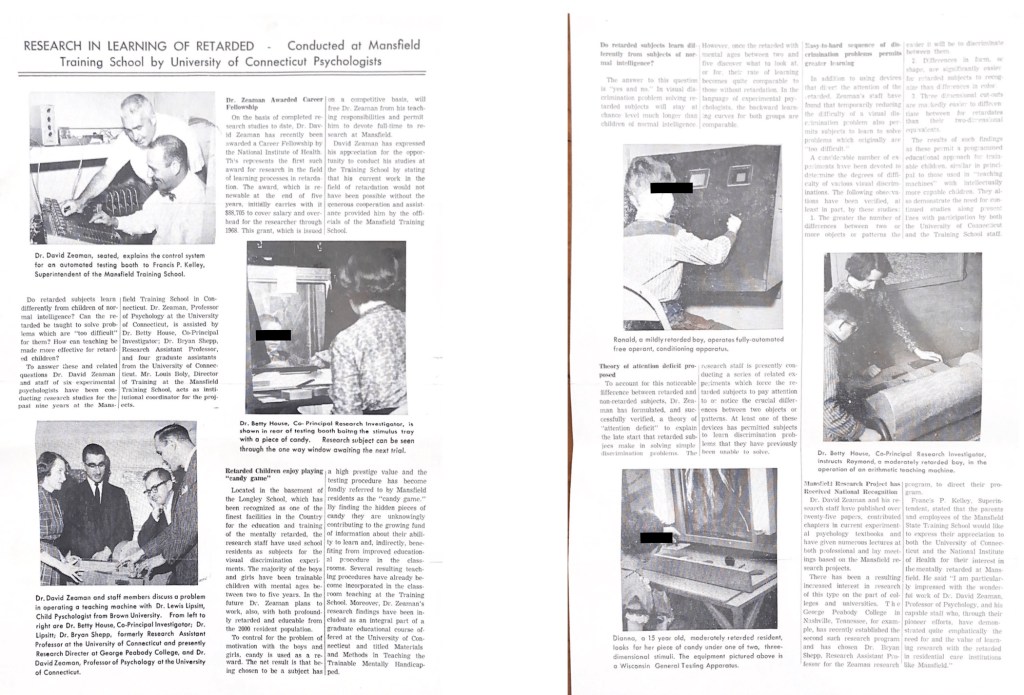

During the height of this abuse, back in the mid to late sixties, the University of Connecticut continued to cultivate their bond with MTS. UConn sent their students there. They worked there and researched there. One key faculty member from UConn that spent a majority of his time at MTS was Psychology professor David Zeaman. In an article detailing Zeaman’s work, it mentions that Zeaman had been conducting research at MTS for 9 years with the assistance of 6 other experimental psychologists. Due to his innovative research, he was awarded a Career Fellowship by the National Institute of Health, which was the first such award for research in the field of learning processes in the field. The award was a salary of $88,705 ($685,750.08 today), intended to cover Zeaman through 1968. This grant would ‘free’ Zeaman from his teaching responsibilities and allow him to do full time research at MTS.

In the basement of Longley School, the research team used the school residents as subject for their visual discrimination experiments. In order to keep the ‘motivation’ of the boys and girls he worked with, he used candy as a reward. In the ‘game’ they would play, the residents would find hidden pieces of candy which Zeaman would use to rank different ways in which they learned to advance strategies for teaching disabled children in the classroom. MTS would then incorporate these findings into the children’s education and alter their curriculum for the sake of Zeaman’s research. Moreover, it seems that Zeaman’s findings were also included as an integral part of UConn’s graduate program through a course titled “Materials and Methods in Teaching the Trainable Mentally Handicapped.”

This research then caused him to develop a theory of ‘attention deficit’ to explain the late start the person would make in solving simple problems. Zeaman and his staff have published over 25 papers, contributed chapters in experimental psychology textbooks, and given numerous lectures based on their research at MTS.

As MTS saw a growth in research and became a national spotlight for its services for disabled people, the establishment of a foundation to maintain funds and donations became necessary. The years 1973 to 1976 saw the birth of an entity that would be known as the “Mansfield Training School Foundation.” Similar to the “UConn Foundation” which was founded by previous (1940) MTS Board of Trustee President, Treasurer, and Auditor Lester E. Shippee in 1962, the UConn Foundation served as a framework for what the MTS Foundation would aspire to be. The UConn Foundation, like any other institutionally related foundation, existed solely to solicit, receive, and administer private gifts and financial resources that provided additional support beyond UConn’s grant income and state funding. The UConn Foundation spent the majority of its existence conducting private fundraising on behalf of the University of Connecticut. Could it be that the former MTS Board of Trustees member, Lester Shippee, aimed to cross over from MTS to UConn by establishing this foundation during the first year of Babbidge’s presidency? Either way, Shippee’s UConn Foundation acted as a blueprint for the MTS Foundation, which will be explored further in “Cross-Institutional Connections” on this website.

1986 and 1987

Spilled (and Spoiled) Milk

In data sheets from Director of the Physical Plant, George Clark Niles to the Director of Administration and Research at the Department of Mental Retardation (DMR), Dr. Eugene Heide, Niles expresses their plan for closing buildings across the MTS campus. On a list of buildings described as ‘abandoned’ versus ‘closed,’ Niles explains that all structures deemed closed will be maintained post-closure by circulating heat within the buildings to prevent rapid deterioration, while abandoned structures would be allowed to deteriorate and fall apart.

That same year, the movement of many MTS clients to group homes and out of the institution left them a surplus of buildings that needed to be maintained if they were to be kept as MTS property. In a letter to the DMR, Assistant MTS Director John Parson reflects on the need to “dispose” of the surplus buildings at the institution via a transfer to other State agencies, auctions to the public, or demolition. The reason was simply because the school was not given funds to continually maintain or upkeep these buildings. Framing this as not being in the best interest to the taxpayers of Mansfield, Parson explains that former staff houses (Birch Cottage, Pine Cottage, Overlook Cottage, Spring Manor Cottage, Hilltop Cottage, and Wayside Cottage) and former client residences (Matthews Hall, Binet, Johnstone, Goddard Hall, and Pavilion) are currently being unused and should be transferred or destroyed. The institution had previously requested demolition funds for Rogers, Storrs, Fernald, and Rubin but their requests had been ignored for at least 9 months. With all the plumbing systems drained and the heat being made to circulate previous staff houses, if the school is unable to transfer these properties quickly they will deteriorate rapidly post-shutdown. In the abandoned properties where residents resided, deterioration had already been occurring for over a year.

With a surplus of property and lack of funding from the State of CT, MTS needed to partner with a State agency that would take some of their buildings. In 1987, rumors began to travel across the Mansfield Parents’ Association at the Training School. These rumors would soon become a reality, as the President of the Association, Mary Lea Johnson, reports to her members that a proposal has been made between MTS and the CT Department of Corrections (DOC) to use the vacant buildings. This is a another connection that we will explore in “Cross-Institutional Connections” on this website.

Shortly after nervous talk surrounding a possible DOC usage of the campus, tensions around food production began to rise between the MTS-UConn partnership. After transferring farmland from MTS to UConn, an agreement was established that UConn would provide dairy and other such products to the residents of MTS after taking over production. From November of 1974 to September of 1987, UConn had been providing MTS with expired and unrefrigerated milk products. In a letter from J.N. Fardal at MTS to a Mr. George Norman at UConn, Fardal recalls speaking to Norman on November 8th of 1974 about receiving milk that was past the due date. George mentioned that this issue would be corrected. In the next milk delivery to MTS (November 11th and 13th), the milk was three days past the expiration date. Fardal expresses that if this issue continues, MTS will deny any and all products that are not below 2 days of the expiration date. Little did Fardal know, however, that this was just the beginning of over 10 years of poor-quality food products that would be delivered to the residents of MTS.

With UConn’s lack of care or attention to the quality of products sent to MTS, the school established a strict policy in 1977 that all products delivered from UConn (milk specifically) must have the date checked and returned to the delivery driver if it has an expiration date any sooner than 3 days prior to the expiration date. So, milk delivered on February 1st, for example, must be dated no earlier than February 4th. While UConn was knowledgeable of everything that was occurring regarding expired milk, the issue persisted to a point where in 1981, MTS began their investigation on the UConn products. The Food Services Department of MTS, thus, began saving any suspected spoiled milk from UConn instead of disposing of it. No MTS member was to dispose of any products until a representative of the Food Services Department had thoroughly inspected it. Prior to this, when milk was disposed of, there was no way to verify the condition or date, and therefore the school could not document the UConn deliveries with proof of the conditions. As evidence of deteriorating food conditions is gathered, Norman is once again notified in March of 1983 of the issues that have been persisting. In this case, bulk amounts of milk and cottage cheese were delivered to MTS without expiration dates (whether they were not printed or removed is unclear). With the dairy products becoming spoiled after a few short days, MTS decided to remove cottage cheese from their menus completely in order to keep their clients safe. Ice cream was also being delivered melted and packaging was “sloppy,” either being poorly sealed or leaking.

Without proper change, MTS began to switch their milk productions and purchases from UConn Dairy to Guida Dairy due to the poor quality of the UConn product in 1987. In a detailed document from the year of 1987, MTS documented every contaminated product they received from UConn:

June 11th, Orange juice was delivered to MTS that was contaminated with bleach.

August 14th, Italian Ice was received in an open truck that was partially defrosted.

August 12th and 13th, Milk (48 degrees-52 degrees) and orange juice (48 degrees-68 degrees) were delivered in an unrefrigerated truck.

August 17th and 19th, Milk delivered in an unrefrigerated truck (48 degrees-50 degrees) and 9 cases short of product. So, aside from leaking containers, puddles of milk, contaminated products laced with bleach, and melted products—MTS received consistently poor treatment despite their countless complaints to UConn. This list only shows the surface of this continued issue. In files between members of MTS, Gene Light detailed dates when poor-quality products were delivered.

With conditions so poor that MTS had to switch their milk provider, this lack of proper care and quality delivered to MTS only further reflects the University’s sentiments towards MTS and its residents. UConn didn’t care enough to ensure MTS residents simply had good food to eat. So, why would they care what happened to the campus that they occupied just years prior? More importantly, since both institutions fell under the care of different State departments, wouldn’t there be some indication of State intervention considering the severity of this issue and negligence on the part of UConn? Unfortunately, the documentation of these issues and correspondence can only reveal that this matter was solely dealt with between the institutions. However, when it comes to the occupation of MTS land, the State of Connecticut faces no hesitancy in regards to becoming involved.

1990s

The Hidden History of MTS and Emergence of “UConn Depot”

Three years before MTS’s final close, one last report was drafted to the Governor of CT, William A. O’Neill. The main goal of this final report was to draft a Master Plan for the use of buildings on the MTS grounds and any recommendations for future movement. MTS, 96 buildings on 896 acres of land, contains buildings from 1919 and many ‘newer’ additions that have appeared over the last 70 years.

With all this land and property, a tentative list of departments that could appear on the MTS campus included: A Natural History Museum, the Frank Ballard Puppet Museum, Internal Audit, Personnel, Medieval Studies, Mail Services, State Archeologist, Institute for Social Inquiry, graduate student housing, and more.

Since court approval of the DOC use of MTS was granted, Governor O’Neil announced the formation of a Task Force on Mansfield Training School. This group, which included state agency heads, local officials, and advocates, was charged with devising a plan for the future of MTS.

The Task Force recommends that UConn and local recreations such as the Department of Recreations and Greater Mansfield Council of the Arts take control over Longley School—a prime buffer building. The public of Mansfield, should also be able to make full use of the gymnasium in the school and auditorium as part of this agreement, which includes athletic fields adjacent to the school. UConn will also be given access and use of the cottages located on Bone Mill Rd that will be vacated by June 1991. UConn anticipates using these cottages as home offices and work spaces for a number of small study centers scattered across the Storrs campus, including graduate housing. Dimmock, though it has a significant amount of asbestos, like all MTS buildings, will also be given to UConn as well as all remaining farmland lying west of Route 32 and east of Route 32. At the end of this report, the Task Force includes budget proposals for the reuse plan and steps moving forward financially. The Task Force recommended two items: an authorization of $1.56 million to enable DMR to renovate 6 buildings for its long term use of MTS; and, an initial authorization of $8 million for the Department of Public Works (DPW) to cover a variety of costs. This would include renovations to Longley, the Brown buildings, and the Bone Mill Road cottages for UConn’s occupancy, and the removal of asbestos from Dimmock. UConn has also estimated that 7 positions and $284,000 in operating costs will be needed in 1991 as they have agreed to assume public safety responsibilities at MTS that previously fell to DMR. While there is no further talk of money transfers to UConn for MTS, it seems interesting to note the State’s consideration of spending such a large amount of money on the reuse of MTS when, for decades, the institution had been filing for basic renovations of their decaying buildings that residents were forced to inhabit.

As the MTS comes to a final close, and UConn takes over most of the operations, the institution remains as desolate and barren as it would have been in those final years before its closure. The rapid deterioration and immense amounts of asbestos has left the campus unusable to UConn. And, while many of the older buildings were registered as historic places in 1987 for their architecture and ‘social/humanitarian’ uses, these buildings have not been upkept. Building constructed between 1800 and 1935 fell into the category of historic places. Some of the buildings included on this nomination form were: Baker Hall, Dimock Hall, Goddard Hall, Knight Hospital, LaMoure Hall, Storrs Hall, Wallace Hall, Tredgold Hall, multiple cottages and barns, Rogers Hall, and more. Therefore, these buildings were protected due to their cultural heritage value. Today, they remain standing, but barely. Though the Mansfield Training School and the University of Connecticut have grown-up together, only one has flourished and survived to the 21st century. So interconnected, yet distant, it is important to note the status of MTS today and acknowledge what has happened to the site.