Written By Ally LeMaster

When I arrived on my second day of our archival visits at the Connecticut State Library, I felt like an archaeologist who exhumed only a few miscellaneous bones of an entire body. I spent my time in between archival visits scouring old Hartford Courant articles, watching videos of “urban explorers” documenting the haunting conditions inside of Knight Hospital, and researching other institutions to try and understand how each bone left behind at Mansfield Training School (MTS) connected. The more I found, the less confident I became in my ability to assemble the skeleton as it once was. I was determined that day to find something more than bones— this time I wanted to leave with a way to piece the story of MTS together.

In the box I searched through, nestled between employee guidebooks and vaguely documented dismissal records, I pulled out a stark white booklet titled “The Mansfielder.” What first stuck out to me was the near-perfect condition these booklets were kept in; many of the documents the research team and I went through were in various states of aging, with most of the files I looked at printed on thin, transparent copy paper. There were dozens of editions of The Mansfielder scattered throughout folders, with some of the same issues even having multiple copies.

Two editions of the Mansfield Training School’s published newsletter “The Mansfielder.” These two issues span from March through September of 1972, highlighting stories such as the construction of new cottages for residents and a Valentine’s Day card drive. Copies of “The Mansfielder” were sent to institutions across the United States, state government officials, and families of the residents.

What I originally believed to be the first edition of The Mansfielder was published in 1972 and was signed by superintendent at the time Francis P. Kelley. Kelley’s time at MTS was marked by his significant attention to public relations, often having legislators, academics, and journalists visit and take guided tours of the institution. The Mansfielder followed exactly what Kelley had set out to do: it gave Mansfield Training School the positive public perception it was desperately in need of after Geraldo Rivera’s exposé of the abuses at Willowbrook State School released that same year.

Each edition of The Mansfielder followed residents and their activities over the course of a couple months and were littered with syrupy sweet headlines:

“Project FOCUS Launches Roller Skating Program”

“Mansfield Artist Sketches Portrait of Governor”

“Project FOCUS Celebrates First Anniversary With Holly Ball”

“Residents to Make Christmas Decorations for Trees”

“Training School Employee Honored as ‘Outstanding’ by the AAMD”

“Technical School Builds Cabins For Summer Camp”

(Project FOCUS or “Forgotten Ones Christmas You Serve” was a program through MTS in the 1960s that started as a way for the University of Connecticut faculty to take “unvisited” residents home for the holidays. It later became a year-round project involving foster grandparents, outings, and donation drives.)

Each headline strikes the balance of positivity and productivity; giving the reader the illusion that a day at Mansfield Training School was filled with hard work and hard play: a narrative that strayed far from reality.

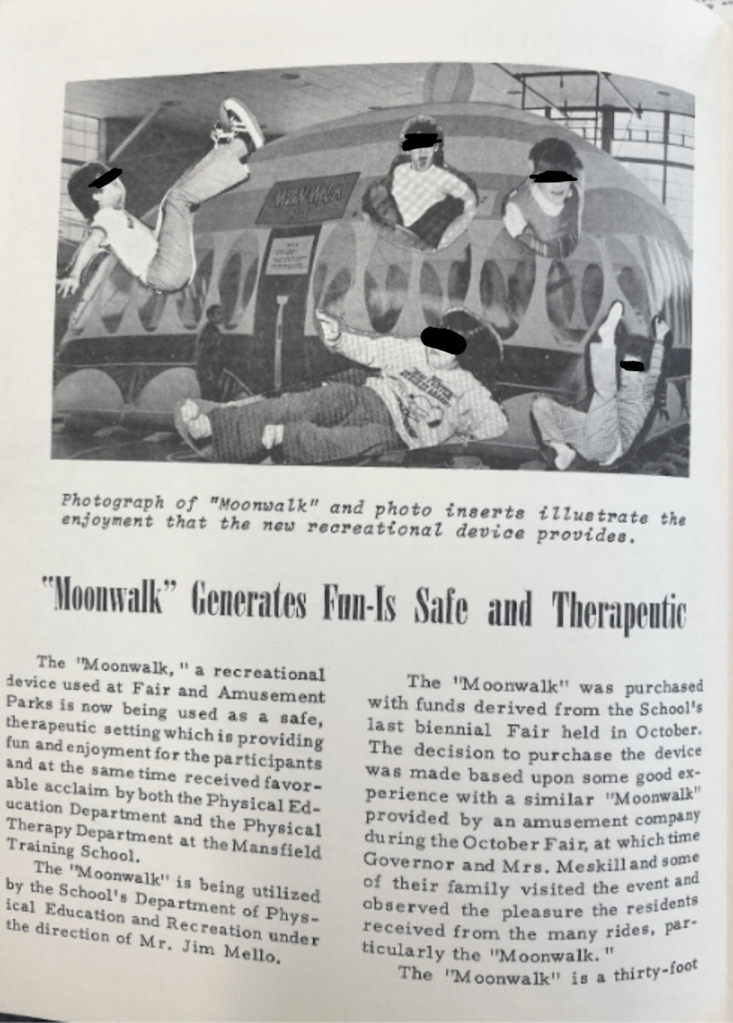

The thin veneer of The Mansfielder begins to dissipate the further you dig into the publication’s issues. The article titled “ ‘Moonwalk’ Generates Fun– Is Safe and Therapeutic” is accompanied by a photoshopped image of residents cut-out and pasted over a picture of a bouncy house to “…illustrate the enjoyment.” The article itself focuses on the physical benefits and fun of the residents’ new bouncy house, but excludes interviews or real-time photographs of the residents actually enjoying it.

In the article “Project FOCUS Launches Roller Skating Program,” The Mansfielder celebrates the donation of 51 pairs of roller skates with a party, but fails to mention how many of the 629 Project FOCUS members used these skates or how long each resident could skate for.

While most of what The Mansfielder spewed out to Connecticut governmental agencies, resident’s families, and other state institutions veered on the line of propaganda, some articles added new life to other documents the research team thought were only dead ends. Before discovering The Mansfielder, I read about new cottages and apartments built by MTS, but found no further information, which led me to believe they simply didn’t exist. However, many of the articles in the publication spotlighted the different out-of-facility living arrangements; their locations, their usages, and which residents were eligible. In addition, the last publication under Kelley’s reign printed out part of his resignation speech, listing what he believed MTS needed to improve on for the future.

The most out of place article in The Mansfielder is titled “Connecticut Legislators Inspect Training School” and describes the awful conditions 55 legislators found while touring the school in 1973:

“The units showed the passage of time with cracked and falling plaster, leaking roofs, crowded living areas and and in general an unpleasant, uninspiring atmosphere. These were units that had been recommended for demolition by previous committees. They saw toilets without seats, ‘gang showers’ and a general lack of privacy…”

At the end of this damning article, The Mansfielder still tries to spin the narrative, “ The feeling among Legislators was that change was necessary and that change must be positive and immediate!”

That article left me with many questions. In the time of institutional exposés, why publicize various problems in a publication meant to showcase the best of the Training School? Is it to garner more donations? Create sympathy? Actually address a problem?

Did The Mansfielder choose to include the least harmful discoveries of the visit? Is the truth of Mansfield Training School so bleak that a positive angle can’t even cover the direness of living conditions?

Will we ever really know?

For a while, I believed The Mansfielder did something other archival documents could not: add to my bones of understanding with muscle and scar tissue— build a fuller story of what happened at MTS. When you create a narrative, albeit a distorted one, you add life to someone’s story that would only be told through numbers; age, years spent at the institution, prescribed milligrams of medication, and time spent in physical restraints.

But that’s the problem. That’s exactly what makes publications like The Mansfielder so dangerous. Any entity who is given the power to be the sole storyteller of another’s life has the ability to make the ugly parts disappear forever. It’s so easy to create an inaccurate perception of the truth as long as you have an interesting story. So how can I lay out the complete story of the body when it was never allowed to speak for itself?In other words, I don’t believe we can exhume the body and reassemble it because the body wasn’t a body to begin with. The truth of Mansfield Training School begins and ends with its residents: people who had lived experiences that we will never fully understand because we were always made to forget. The purpose of doing archival research on institutions is not to recreate stories of residents, otherwise we’d be just as bad as The Mansfielder. Our work is built on challenging erased narratives by analyzing information and providing real accounts to what real residents went through. Our narrative is their narrative. All we can do is provide you with context from what we’ve learned.